Artistic Inspirations

Sandow Birk’s Vision of Dante

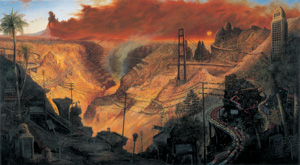

California artist Sandow Birk has placed a uniquely American stamp on Dante’s vision and our reading of the Divine Comedy. His edition of the Divine Comedy features a new vernacular translation and lithographs that depart satirically from Gustave Doré’s famous Dante wood engravings (see Inferno, Canto 13, Purgatorio, Canto 31 and The Imperial Eagle, Paradiso Canto 20) and recasts Dante’s concept of the afterlife in a recognizable—if often appalling—urban America. Likewise, in Birk’s triptych of large-scale paintings treating each of the three canticles of Dante’s poem, he makes a nod to the nineteenth-century Hudson River School, and a vision of the American landscape that encouraged settlement of a pristine “empty” wilderness from the Catskills to California.

Just as Dante’s poem (along with its encyclopedic look at religion, history, and mythology) is a snapshot of his own political and social reality, so Birk’s art addresses the societal ills of his own moment. But where Dante’s poem aspires to present God’s ordering of the next world towards the redemption of a sinful humanity, Birk presents a different world order, tied to the religious underpinnings of Manifest Destiny and American Exceptionalism, and the human reality of dispossession, economic inequity, and pollution that trails in the wake of this ideology.

Sandow Birk

American, born 1962

Inferno, 2003

Oil and acrylic on canvas

66 x 120 inches (167.64 x 304.8 cm)

Courtesy of the San Jose Museum of Art

Gift of the Lipman Family Foundation, in honor of the San Jose Museum of Art’s 35th anniversary

(1 image)

Birk’s painting of Inferno finds Dante and Virgil silhouetted against a vast Grand Canyon-esque vista of decaying American consumerism and car culture, dotted with the vestiges of triumphal American engineering. A ruined Golden Gate Bridge juts across the chasm; the proud but disconnected faces of American presidents survey the scene from a distant Mount Rushmore. Although Birk’s trilogy was painted in 2003, the general devastation and the ash that pours from a distant volcano obscuring the sun takes on contemporary relevance, recalling rampant California wildfires fanned by the forces of climate change.

Here, the “shadowed forest” Dante describes in Canto 1 is not a wilderness at all; Birk’s Inferno is an urban journey. Accordingly, the very mouth of hell is an underground parking ramp complete with Birk’s translation of Dante’s inscription, “This way to the city of pain/Thru here ceaseless agony awaits”. Above it, a Walmart sign drives the point home.

Sandow Birk

American, born 1962

Purgatorio, 2003

Oil and acrylic on canvas

96 x 120 inches (243.84 x 304.8 cm)

Courtesy of the San Jose Museum of Art

Gift of the Lipman Family Foundation, in honor of the San Jose Museum of Art’s 35th anniversary

(1 image)

Here, Dante and Virgil view Purgatory as if from the Hollywood Hills where they are dwarfed by a new Dante-specific version of the famous “Hollywood” sign. Like the fabled Tower of Babel, Purgatory is a monument to human failings, and Dante will encounter the seven deadly sins as he climbs each level, each penitent soul he will meet there toiling in hope of redemption.

The Mountain of Purgatory is a vertical Los Angeles of sorts, wreathed in freeway ramps. Traffic helicopters swoop, and even the Goodyear Blimp, a staple of televised stadium events, arrives from the distance. Thus, this part of Dante’s narrative devoted to human struggle against sin and error is bracketed by references to ubiquitous American mass media—film and television.

Sandow Birk

American, born 1962

Paradiso, 2003

Oil and acrylic on canvas

66 x 120 inches (167.64 x 304.8 cm)

Courtesy of the San Jose Museum of Art

Gift of the Lipman Family Foundation, in honor of the San Jose Museum of Art’s 35th anniversary

(1 image)

Birk’s vision of Paradiso, the heavenly realm of the blessed, has a decidedly New York flavor. The Brooklyn Bridge spans a river ahead of two other New York bridges including the Hell Gate Bridge from Astoria, Queens—a humorous reference to Hell in a painting supposedly devoted to Heaven.

These New York elements blend with buildings and commercial signage reminiscent of Tokyo in the left foreground. Highways and bridges teem with orderly streams of cars. Is the artist’s vision of Paradise one of economic health and urban harmony? Whatever the case, the vision is a fragile one: at left, the sun is already obscured by a brown cloud reminiscent of the volcanic ash in Birk’s painting of Inferno.

Sandow Birk

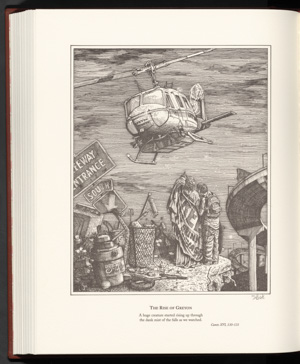

American, born 1962The Rise of Greyon, Inferno, Canto 16,

in Dante Alighieri, Inferno, Brisbane, CA: Trillium Press, 2003.

Lithograph

Image: 10 x 8 1/8 inches (25.4 x 20.64 cm)

Cornell University Library, Rare and Manuscript Collections

(3 images)

In Inferno Canto 16, the beast Geryon arrives to carry Virgil and Dante from the circle of the violent down to the circle of the fraudulent. In Dante’s telling, Geryon is the perfect embodiment of fraud: a fantastical winged creature with the body of a dragon, the front paws of a lion, a long venomous tail—and the face of an honest man. But in Birk’s envisioning, Geryon takes a widely-recognized urban form: that of a helicopter. In Birk’s translation of Dante, “Greyon” arrives “with its arms spread out, clawing, and its legs doubled up.”

Sandow Birk

American, born 1962

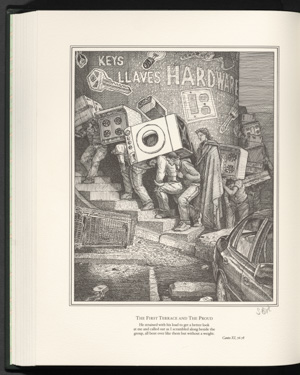

The First Terrace and the Proud, Purgatorio, Canto 11,

in Dante Alighieri, Purgatorio, Brisbane, CA: Trillium Press, 2004.

Lithograph

Image: 10 1/4 x 8 1/4 inches (26.04 x 20.96 cm)

Cornell University Library, Rare and Manuscript Collections

(2 images)

At the end of Purgatorio canto 11, Dante and Virgil encounter the penitent prideful (see Alessandro Vellutello, Inferno, Canto 20. The Circle of Soothsayers… and Michael Mazur, Inferno II: XX The Seers, from L”Inferno of Dante) who carry the weight of their sins on their backs. Birk’s version departs from an illustration by Gustave Doré. Here, instead of the heavy stones marking these sinners’ egotism that Dante describes and Doré draws, Birk’s penitents are crushed by the weight of household appliances, symbols of American consumer culture, and perhaps the consuming pursuit of the perfect home.

Sandow Birk

American, born 1962

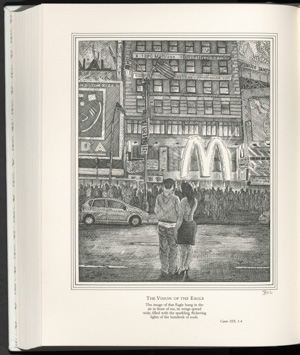

The Vision of the Eagle, Paradiso, Canto 19,

in Dante Alighieri, Paradiso, Brisbane, CA: Trillium Press, 2005.

Lithograph

10 3/8 x 8 3/8 inches (26.35 x 21.27 cm)

Cornell University Library, Rare and Manuscript Collections

(2 images)

In Paradiso canto 18, Dante encounters a throng of heavenly souls who gather to form a Latin inscription, which fades away, leaving only the letter M (for Monarchy, relating to Dante’s beliefs in the primacy of kingly rule). (See also Divina commedia, Foligno, Johann Neumeister, 1472, Francesco Fontebasso, The Imperial Eagle, Paradiso Canto 20, Gustave Doré, The Imperial Eagle, Paradiso Canto 20 and Monika Beisner, The Imperial Eagle, Paradiso Canto 20.) That letter M then morphs into a giant Imperial eagle, underscoring this concept. As canto 19 opens, Dante and Beatrice behold the eagle, which Birk presents in the guise of the most recognizable letter M in the world: the Golden Arches of McDonald’s, in its own way a symbol of worldly dominance.