Selected Themes from the Divine Comedy

Dante and the Body

Dante’s Inferno expresses the bodily suffering of sinners in many compelling ways. At the same time, whether those he meets on his journey evoke scorn or pity, all but a select few retain their humanity in Dante’s eyes. Accordingly, artists have used the human form as an expressive tool, distilling Dante’s narrative to its effects on the body.

American poet and Dante translator John Ciardi believed that modern art enabled artists to push beyond the limitations of literal illustration: “…only so could the graphic artist be free to image forth the inwardness of things as Dante had imaged it forth in poetry.”

In the mid-twentieth century—at a moment when the world of art largely sought abstraction—artists like Rico Lebrun and Leonard Baskin, both committed to the expressive graphic potential of the human form, turned to Dante. It is hardly coincidental that both were also compelled to depict the horrors of the Holocaust and the Atomic Bomb that had literally brought Hell to life on earth. In our own day, artists like Kara Walker map the struggle of Dante’s journey onto the Black female body, understanding, as Dante did, the power of hardship to hone the artist’s expressive powers and social impact.

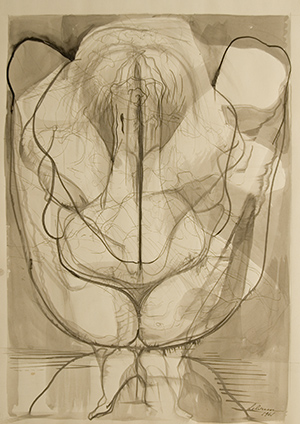

Rico Lebrun

American, born Italy, 1900–1964

Bolgia of Ice, 1961

Ink, ink wash, and pencil

24 3/4 x 16 3/4 inches (62.9 x 42.5 cm)

Syracuse University Art Museum

Gift of Whitney Blake and Allan Manings

(1 image)

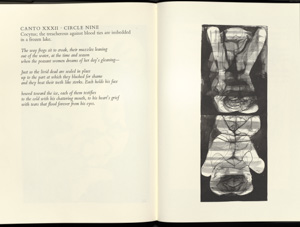

Rico Lebrun

American, born Italy, 1900–1964

Canto 32, Circle Nine, from Drawings for Dante’s Inferno, 1963

Lunenberg, Vermont: Stinehour Press

Cornell University Library, Rare and Manuscript Collections

(2 images)

Like the powerful drawings of his Italian artistic predecessor, Michelangelo, Rico Lebrun’s art is relentlessly figural. About this fascination, Lebrun wrote: “the human form, plastically translated into terms of its own image and likeness, is…the only realm proper to the art of image making.” Here, Lebrun’s focus on the body delves expressively into Dante’s vision. The bolgia of ice refers to the lowest circle of hell, reserved for traitors to kin, who spend eternity immobilized in a frozen lake. Dante’s ultimate vision of infernal torment is not by fire but by teeth-chattering, shuddering cold. Lebrun evokes the corporeality and gravity of these sinners’ bodies, contorting them into impossible positions but still conveying their shame by the bowing and covering of their heads.

Lebrun’s series of drawings came hard on the heels of two other drawing series treating human suffering: one of the crucified Christ surrounded by his lamenting followers, and a second memorializing victims of the Holocaust.

The Syracuse University Art Museum holds a significant corpus of Lebrun’s drawings, including several on Dante themes.

Leonard Baskin

American, 1922–2000

Sinner Reversed in Pit (Inferno, Canto 19, lines 22-24), 1969

Pen, ink, and wash

38 5/8 x 26 3/16 inches (98.1 x 66.5 cm)

Herbert F. Johnson Museum of Art, Cornell University

Gift of Janet Marqusee, Class of 1952, and John E. Marqusee, Class of 1951

(1 image)

Like his contemporary Rico Lebrun (see Rico Lebrun), draftsman, painter, and sculptor Leonard Baskin dedicated his art almost exclusively to the human body and its expressive potential. In this large-scale drawing for a 1969 edition of the Divine Comedy, Baskin ingeniously chose to focus not on Dante and Virgil’s view of the Simonists’ feet projecting above the surface (see Dante and Virgil Encounter the Simonists), but on the sinner himself in the pit. His body spills outside the frame, magnifying his woe at having committed this fraud against the church.

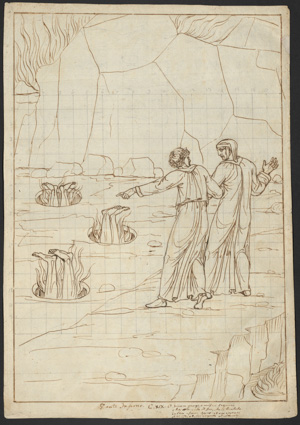

Unidentified artist

Italian, early 19th century

Dante and Virgil Encounter the Simonists (Inferno, Canto 19)

Pen and brown ink

18 x 12 1/2 inches (45.7 x 32 cm)

Cornell University Library, Rare and Manuscript Collections

(1 image)

This drawing is one of a series rendered in a Neoclassical style (see Dante from Classical to Romantic) rediscovered in Willard Fiske’s Dante scrapbooks. In the eighth circle of hell, where the fraudulent are punished, Dante (at right) and Virgil come across the Simonists—those who buy or sell spiritual privileges or offices. They are so called after Simon Magus, who tried to bribe Christ’s followers Peter and Paul to teach him how to perform miracles; Dante includes some very powerful people among their ranks in Hell. Because of their reversal of Christian values, they are condemned to spend eternity upside down in fire. The stone pits mock the water-filled basins used in Christian baptism.

Kara Walker

American, born 1969

Dante (Free from the Burden of Gender or Race), 2017

Oil stick and Sumi ink on paper collaged on linen

48 x 42 inches (121.9 x 106.7 cm)

Courtesy of the artist and Sikkema Jenkins & Co., New York

(1 image)

Active since the mid-1990s, Kara Walker has both unflinchingly and shrewdly chronicled the brutality visited on the Black body in America via the Atlantic slave trade and the plantation economy. This mixed-media work debuted in a September 2017 exhibition at a time when the nation had just witnessed the violence of a white supremacist rally at Charlottesville, Virginia over the preservation of Confederate symbols. Accordingly, in her artist’s statement for the exhibition, Walker wrote: “I write this knowing full well that my right, my capacity to live in this Godforsaken country as a (proudly) raced and (urgently) gendered person is under threat.” Here, the black void in which the female figure twists might be read as a literal evocation of the darkness of Dante’s underworld. But, As Aruna d’Souza observes, Walker seems instead to be saying that, despite the constant weariness that comes with being Black and a woman in America, “to be free from those ‘burdens’ would be its own kind of hell.”[1]

Footnotes

[1] https://www.4columns.org/d-souza-aruna/kara-walker. Accessed June 28, 2021. ↩