Artistic Inspirations

Gustave Doré

By the age of sixteen, Gustave Doré (1832-1883) was already the highest paid illustrator in France. At twenty-two, he entered the field of literary engravings. Soon, he approached Louis Hachette, the first publisher to contract with railway companies to create station bookstalls. In addition to travel guides for train passengers, these outlets sold novels by popular authors such as Charles Dickens or George Sand—alongside works from the children’s series La Bibliothèque rose—all for two or three francs. By contrast, Doré’s project was ambitious and expensive: illustrating Dante’s Inferno, he sold a “sublime” folio volume for a hundred francs. Understandably, Hachette turned him down, and Doré had to cover the cost of producing of the first (1861) limited edition, with seventy-one plates! It was a success, and Hachette agreed to reprint the Inferno volume, followed in 1868 by a second volume containing both Purgatorio and Paradiso. Printed in multiple European languages, they became international best-sellers. Fiske acquired editions in Dutch, French, German, Italian, Portuguese, Russian, Spanish, and Swedish for Cornell.

According to Aida Audeh, “Of Doré's literary series, few enjoyed as great a success as his Commedia illustrations. Characterized by an eclectic mix of Michelangelesque nudes, northern traditions of sublime landscape, and elements of popular culture, Doré's Dante illustrations were considered among his crowning achievement.”

Given Doré’s importance to the modern visualization of Dante, his illustrations appear in various places in the exhibition.

Gustave Doré

French, 1832–1883

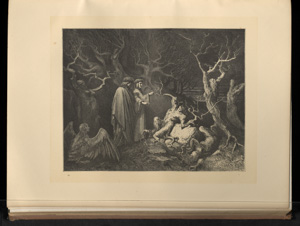

Inferno, Canto 13: The Wood of the Suicides

in De hel van Dante Alighieri; in de dichtmaat van 't oorspronkelijke vertaald door Jan Jakob Lodewijk ten Kate; met platen van Gustave Doré

Leiden, Netherlands: A.W. Sijthoff, 1877

Wood engraving

Image: 9 1/2 x 7 1/2 inches (24.13 x 19.05 cm)

Cornell University Library, Rare and Manuscript Collections

(1 image)

Romantic literature and art—such as Grimm’s Fairy tales—revived the medieval tradition of the forest as the site of supernatural occurrences. Accordingly, in Doré’s image of Virgil and Dante’s entrance into the wood of the suicides, he crafts a foreboding net of strange black misshapen trees with poisonous branches barren of fruit. Here Harpies nest, feeding on the transformed souls of those who have committed the sin of violence against themselves. These trees are themselves human beings; Dante, against Virgil’s advice, snaps off a twig, prompting this compelling description:

As from a sapling log that catches fire

along one of its ends, while at the other

it drips and hisses with escaping vapor,

so from that broken stump issued together

both words and blood; at which I let the branch

fall, and I stood like one who is afraid.

Gustave Doré

French, 1832-1883

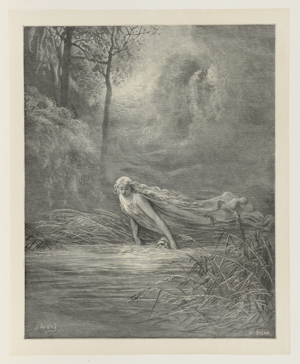

Purgatorio, Canto 31: Dante Baptized a Second Time

in Le Purgatoire et le Paradis de Dante Alighieri, Paris: Hachette, 1868

Wood engraving

Image: 9 3/4 x 7 3/4 inches (24.77 x 19.69 cm)

Cornell University Library, Rare and Manuscript Collections

(1 image)

For Dante’s illustrators, Beatrice is a complex figure, both priestess of love and angel of salvation. In Purgatorio Canto 30, Dante’s beloved chastises him for having loved others after her death. Beatrice subsequently takes a more benevolent outlook in Canto 31, offering Dante both amnesia and forgiveness through a second baptism. She plunges him, up to his throat, in the waters of Lethe (λήθη = the river in Greek mythology whose name means “oblivion.”) Doré’s image has a Pre-Raphaelite flavor. One thinks of Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s 1863 painting, Beata Beatrix (see Yasumasa Morimura, Portrait (Poppy)) — a tribute to Rossetti’s deceased wife. The flowing hair and association with water also points to Botticelli’s painting, The Birth of Venus, beloved of the Pre-Raphaelite painters.

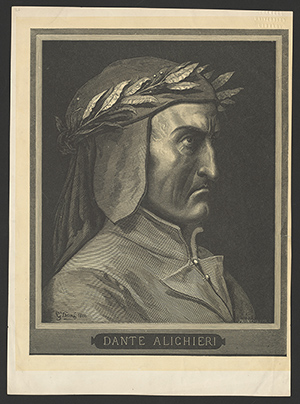

Stéphane Pannemaker

Dutch, 1847–1930

and Gustave Doré

French, 1832–1888

Dante Alighieri, ca. 1860

Wood engraving

Image: 11 1/2 x 9 1/8 inches (29.21 x 23.18 cm)

Cornell University Library, Rare and Manuscript Collections

(1 image)

Doré designed this portrait of Dante as the frontispiece to his 1861 illustrated edition of Inferno. In it, he draws upon by then common conventions for depicting the poet, including the laurel crown and the medieval cap with earflaps. A key departure from these models, however, is the poet’s upward gaze, which seems to indicate a direction of his intellectual and spiritual energies toward the divinely-inspired journey he will undertake as pilgrim.

Furthermore, Doré was a great admirer of French writer Honoré de Balzac (1799–1850), and produced more than four hundred illustrations for a posthumous edition of Balzac’s Contes drôlatiques in 1855. This being the case, Balzac’s description of Dante from The Exiles, 1831, was assuredly in Doré’s mind as he crafted this compelling portrait:

Every feature was in harmony with this eye of lead and of fire, at once stern and calm. [...] The nose, narrow and aquiline, was so long that it seemed to hang on by the nostrils. The bones of the face were strongly marked by the long, straight wrinkles that furrowed the hollow cheeks. Every line in [his] countenance looked dark.