General Introduction

Visions of Dante: Cornell Joins the Commemorations of Dante’s 700th Death Anniversary

In a 1900 issue of the student-produced Cornell Magazine, Library curator Theodore W. Koch wrote, “It might be well for Cornellians and Ithacans similarly interested in Dante to petition the University Trustees to provide for some public exposition of Dante's life and work.” More than a century later, the 700th anniversary of Dante Alighieri’s death is an ideal opportunity to exhibit the largest Dante collection in North America.

What is the Divine Comedy?

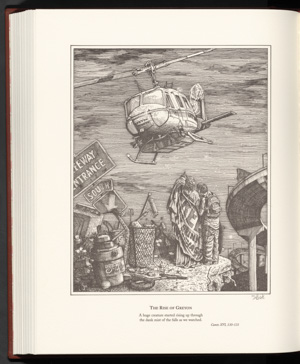

Sandow Birk

American, born 1962The Rise of Greyon, Inferno, Canto 16,

in Dante Alighieri, Inferno, Brisbane, CA: Trillium Press, 2003.

Lithograph

Image: 10 x 8 1/8 inches (25.4 x 20.64 cm)

Cornell University Library, Rare and Manuscript Collections (3 images)

Dante Alighieri (Florence, 1265–Ravenna, 1321) is the greatest writer in the Italian language. A political and religious thinker, diplomat, knight, and philologist, as well as a poet, Dante wrote his masterwork, The Divine Comedy between 1304 and 1321 while living in political exile, as well as spiritual disarray and poverty. This very long narrative poem (14,233 verses of eleven syllables) tells the story of Dante’s adventurous journey through Hell, Purgatory, and Paradise. The three parts of the poem represent a progression from indifference, fear, and disgust, to penitence, forgiveness, and the soul's heroic and luminous ascent to God.

As both the main character and the narrator of the Divine Comedy, Dante has three successive guides: in Inferno, this is Virgil (70-19 BCE), the “divine” master of epic poetry in Latin. The second guide, both in Purgatorio (where, since 1245, some of the dead were supposedly subjected to a trial that could be shortened by the prayers and good actions of the living) and in Paradiso, is Beatrice. Dante had met a “real” Beatrice—Beatrice di Folco Portinari, when they were both nine years old. He always remained in love with her, even after her premature death in 1290. In the Divine Comedy, Beatrice is Dante’s main confessor, intercessor and even (as imitator Christi), savior. Harold Bloom claimed that “Beatrice is the signature of Dante's originality, [the] most audacious act of transforming his inherited faith into something much more his own.” The third guide, in the last three cantos of Paradiso, is St. Bernard of Clairvaux (1090-1153), the theologian of Divine Love and a famous iconoclast, who regarded art as a distraction to devotion and the Adoration of the Cross. This may partly explain why Paradiso is difficult to visualize and illustrate.

The term Commedia refers to Dante’s use of a “median style,” mixing the “elevated style” of the epic poem with irony and humor. Besides, unlike a tragedy, this journey “ends well” for Dante the pilgrim, who becomes realigned with God’s love. Dante’s first biographer, Boccaccio, added “Divine” to the poem’s title in 1373.

Why “Visions of Dante?”

First, T.S. Eliot reminds us that Dante “lived in an age in which men still saw visions”, and that his poetry often stemmed from that “disciplined kind of dreaming.” Such “visions” never ceased to impress and inspire other dreamers and poets. In 1905, a college student named Ezra Pound wrote to his mother, “I shall continue to study Dante and the Hebrew Prophets.”

Second, Dante is a very effective visual poet. As Eliot also noticed, his characters are often defined by their gaze — most memorably, in Purgatorio 6, we see the 13th century troubadour Sordello watching Virgil and Dante like a couchant lion on guard. No need to know the meaning of “couchant” in medieval heraldry to visualize the scene and feel the tension! Similarly, one does not need to be familiar with the palio del drappo verde, a famous horse race in Verona, to perceive the painful irony in Inferno 15: Dante’s beloved professor, Brunetto Latini, is tortured forever in Hell as a sodomite. The reason why he keeps running so fast in the desert is the burning sand under his feet. However, he may look, at first sight, like a running champion, one of those who wins the green cloth, not one who loses.

Finally, Dante is an endless source of inspiration for visual artists, from manuscript illuminators and book illustrators to filmmakers. From Sandro Botticelli to Kara Walker, artists have interpreted and transformed the Divine Comedy according to their own personal language, memories, and perspective on life and society.

The exhibition is organized by gallery, first to provide a history of the Dante collection at Cornell, and next to communicate Dante’s cultural significance, while acknowledging political issues related to his iconic status across seven centuries. Continuing onward, an understanding of medieval theories of vision situates Dante in his own time while setting the stage for subsequent illustrators’ and artists’ encounters with the Divine Comedy from the Renaissance in Europe up until the present day.

We hope you will enjoy the exhibition and form your own “Visions of Dante”!