The Fame of Dante in Italy and Worldwide

Preacher of the Gospel and/or Prophet of New Times?

As Zane Mackin pointed out, Dante thought about the conflation of the two roles, the preacher and the poet. In the Divine Comedy, he used compositional techniques of the sermon (short passages of the Bible followed by arguments, sub arguments, hypothetical dialogues on theological matters…). He also portrayed himself as a follower of John the Apostle in Paradiso, 26: You set it [the Commedia] forth to me in the beginning of your great message, which, more than any other herald did, proclaims the mystery of this high place on earth. Accordingly, one often finds Dante’s poetry scribbled into the marginalia of sermon collections. However, other theologians viewed Dante with suspicion. In 1329, the Dominican Guido Vernani compared Dante’s poem to the treacherous songs of the Sirens!

The traditional world of medieval theology blended with the rediscovery of classical Antiquity. According to Ernst Robert Curtius, it is Dante who elevated himself to the rank of a classic “with timeless authority.” In Inferno 4, Dante elected himself to the company of the five most eminent poets of Antiquity—Homer, Virgil, Ovid, Horace, and Lucan) in the following terms: “They made me one of their company, so that I became the sixth amidst such wisdom.” Italian became the equivalent, in dignity, of Greek and Latin.

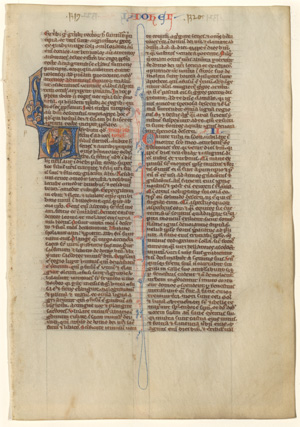

Workshop of William de Brailes, Oxford

English, active ca. 1230 – ca. 1260

Bible leaf showing Joel 1:1–3:14, ca. 1240

Colors and gold on vellum

7.3 x 5.3 inches (18.5 x 13.5 cm)

Cornell University Library, Rare and Manuscript Collections

(2 images)

This illuminated initial “V” begins the phrase “Verbum Domini…” (The word of the Lord). William de Brailes is one of the few 13th-century English illuminators known by name. He maintained an active workshop at Oxford ca. 1238-52. Biblical prophets were perceived as models for the preaching monks, and possibly for poets such as Dante.

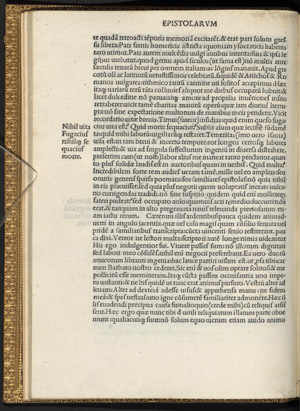

Francesco Petrarca

Italian, 1304–1374

Passage from a letter in Epistolae Familiares

Venice: Joannes and Gregorius de Gregoriis, 1492.

8 1/2 x 6 1/4 imches (21.59 x 15.88 cm)

Cornell University Library, Rare and Manuscript Collections

(3 images)

In this 1347 letter, Petrarch claims that high poetry in Italian “was reborn” (renatum est) in Sicily, in the 12th century, and that from there it spread across Italy. Historically false, this claim is very important, as it linked the Renaissance with the triumph of lyrical and epic genres in the vernacular (in volgare). Dante, according to Petrarch, was “the master of our vernacular literature,” and justifiably he was the most commented upon (there were already twelve commentaries of the Divine Comedy by 1400.)

Like most Renaissance humanists, Petrarch did not admire Dante without reservations, however. He criticized the use of such vulgar terms such as merda (shit), and his association with medieval scholasticism. Besides, he was uncomfortable with Dante’s early popularity among the lower classes: “I envied him the applause and raucous acclaim of the fullers, tavern keepers, and woolworkers!” (Familiares, 21:15.).

Paolo Attavanti

Italian, 1445-1499

A Collection of Lenten Sermons, Quadragesimale de reditu peccatoris ad Deum, Milan, 1479

10 1/2 x 8 inches (26.67 x 20.32 cm)

Cornell University Library, Rare and Manuscript Collections

(4 images)

In 1894, Willard Fiske wrote, “I came across a copy of Attavanti and was struck by the extensive use made by him of Dante, of whom he cites about 1,254 verses (it seems probable that Attavanti had composed a commentary on Dante and incorporated part of it in his Lenten sermons.)”

Attavanti was a member of the Servites, a mendicant preaching order. After his law degree, he joined the community of Santa Annunziata in Florence in 1481 and became a protégé of Lorenzo de’ Medici. In his sermons, he referred constantly to the Biblical Prophets and Fathers of the Church, but also to non-Christian authors such as Plato, Aristotle, Virgil, Averroes. The most quoted author, however, was Dante.

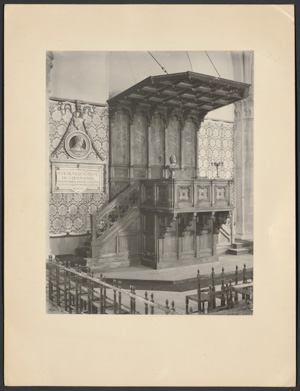

Unidentified photographer

Italian, 19th century

The Sala di Dante (Dante Hall) in Orsanmichele, ca. 1899-1900

Gelatin silver print

11 x 15.7 inches (28 x 40 cm)

Cornell University Library, Rare and Manuscript Collections

(1 image)

The public reading of Dante’s Divine Comedy is a ritual that goes back to the fourteenth century to Boccaccio, who lectured on the poem from the pulpit of San Stefano di Badia church in Florence. More than four centuries later, Fiske attended similar lectures delivered from this speaking platform in the Dante Hall in nearby Orsanmichele. Recently, the actor Roberto Benigni revived the tradition. More than a million people have attended his performances live since 2006; millions more have tuned into them on television—a testimony to Dante’s status as an icon of Italian culture.