Dante from Manuscript to Printed Book

Incunables as Books of Transition

Dante Alighieri

Divina commedia

Foligno, Johann Neumeister, 1472

Cornell Library, Rare and Manuscript Collections

(2 images)

This, the first printed edition of Dante’s Divine Comedy, was printed a scant two decades after moveable type was first employed in Europe in an out-of-the-way place by an itinerant German printer whose relationship to Foligno ended after this one publication. The Foligno Dante edition helped Dante’s poem make the quantum leap from individual manuscript copies—treasured by scholars and collectors of means—to a much broader readership, and it spurred a steady flow of further editions in Italy over the next seventy-five years. Cornell’s first librarian Willard Fiske obtained the book for the University in 1893, in part spurred by the knowledge that his Harvard University Library counterpart had been unable to obtain one—a competitive demonstration important for a young university still establishing itself.

Cornell’s copy is unique in that its margins feature the full transcription of a fourteenth-century commentary by Neapolitan scholar Guglielmo Maramauro (ca. 1317–1380 CE), of which only the Inferno portion was previously known. This important scholarly find is heightened all the more by the unknown transcriber’s practice of annotating the book with marginal drawings copied from his source that served not only as aids to his own understanding of Dante, but also as instructions for subsequent readers. In addition to diagramming the levels of Hell, Purgatory, and Paradise, we find such drawings as the one accompanying the passage in Paradiso 18, in which a group of souls unite to form a letter M. This stands for “Monarchia,” underscoring Dante’s political belief that the world should be ruled by a temporal king or emperor. This letter M, in Dante’s vision, then morphs into the shape of an eagle, the symbol of the Holy Roman Empire in Europe (see also exhibition items from Monika Beisner, Francesco Fontebasso, Gustave Doré, and Leonard Baskin). The annotator’s drawing shows how the shape of an eagle with wings spread (and appropriately crowned) can easily be derived from the shape of the letter M.

Much more about the significance of the Cornell volume can be learned from Dr. Natale Vacalebre in the exhibition preview for Visions of Dante, and in his intensive scholarship about the volume.

Dante Alighieri, and Cristoforo Landino.

La Commedia.

Published by Bonino Bonini, Brescia, 1487

Image: 10 3/8 x 7 inches (26.35 x 17.78 cm)

Cornell Library, Rare and Manuscript Collections

(4 images)

The Brescia 1487 edition of the Divine Comedy is the first extensively illustrated printed edition of the Comedy. Published by Bonino Bonini, a Croatian émigré working in this regional center in the north of Italy, it achieves splendid successes, but it also falls short in ways that indicate difficulties with schedule and budget.

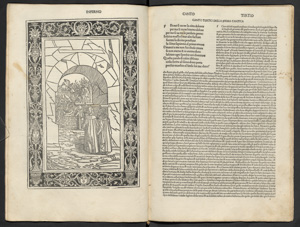

The first illustrated opening reveals the transitional practice of adding a lavish woodcut illustration (the new technology) while leaving spaces for hand illumination of initial capitals (the centuries-old practice); in this case, the initial letter N that starts the entire poem. But unlike the Florence 1481 edition (see exhibition item) on which most of the first nineteen woodcuts of this edition are based, Bonini seems to have planned to provide an illustration for every single canto in the Comedy. In the end, he accomplished 68 woodcuts, in the process completely representing Inferno and Purgatorio and offering one image for Paradiso. But the undertaking seems to have been fraught. Some woodcuts show up-to-the-moment artistic skill and perspective, while others evidence less accomplished hands.

The fascinating woodcut for Inferno, Canto 3, in which Dante and Virgil cross the threshold into hell to begin their journey, seems to be modeled on a manuscript created for Federigo da Montefeltro, Duke of Urbino, now in the Vatican. The composition here allows us to look over Dante and Virgil’s shoulders as they walk into Hell.

The blank nameplates above the heads of the figures appear only in the first four woodcuts—after which a different woodcut artist takes over. We can surmise that these nameplates were initially intended to continue throughout. Were they intentionally left blank for an illuminator, or perhaps the book’s owner, to complete, as an interactive aid to the reader’s understanding and memory?

Dante Alighieri, and Cristoforo Landino.

La Commedia.

Published by Bernardus Benalius

and Matteo Capcasa,Venice, 1491

Page: 11 3/4 x 8 inches (29.85 x 20.32 cm)

Cornell Library, Rare and Manuscript Collections

(2 images)

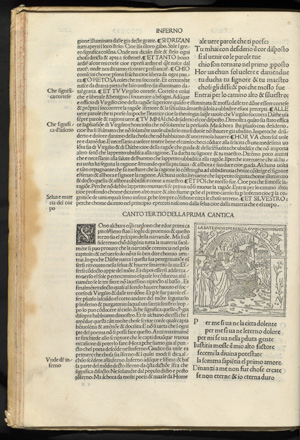

The first Venetian illustrated edition of the Divine Comedy drew heavily on both the 1481 Florence and 1487 Brescia editions. But with the exception of three main woodcuts that open each canticle, the woodcuts in this edition are smaller vignettes [featured image and opening] that seem to serve more to orient the reader, faithfully labeling Dante and Virgil with a “D” and a “V” above their heads, in emulation of the practice begun with fourteenth-century manuscripts. After all, as Pieter Brieger observes, “Dante’s work was accepted as an authoritative account of a journey, granted him by God.” Lucia Battaglia Ricci has observed these labels also help the reader to separate the “primary story” of Dante’s own journey from the many “secondary stories” recounted by the various personages they encounter along the way (see also Initial woodcut to Paradiso and Initial woodcut to Inferno).

Dante Alighieri, and Cristoforo Landino.

Initial woodcut to Paradiso, in La Commedia.

Venice, 1493

Image: 9 1/2 x 6 inches (24.13 x 15.24 cm)

Cornell Library, Rare and Manuscript Collections

(1 image)

Dante Alighieri, and Cristoforo Landino.

Initial woodcut to Inferno, La Commedia.

Venice, 1529

Image: 10 1/2 x 7 1/8 inches (26.67 x 18.1 cm)

Cornell Library, Rare and Manuscript Collections

(1 image)

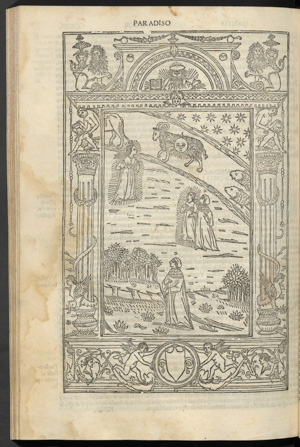

Both of these Venetian editions of the Divine Comedy derive the compositions of their full-page woodcuts at the beginning each canticle from the first Venetian edition of 1491 (see exhibtion item). In the Paradiso woodcut, Dante begins his journey up into heaven with Beatrice, who stops to behold the sun (which, since it is March, is in the constellation of Aries, the Ram). The woodcut border surrounding this image features standard details recalling classical antiquity, the main source of knowledge for all learned people at the time. These include the Roman columns entwined by the tails of harpies, the putti holding the shield at the bottom, and the Roman-style profile portraits. However, the top of the border still presents the image of God the Father looking down from heaven, a typical way of surmounting altarpieces in churches of the time to communicate that the main scene below has been divinely ordained.

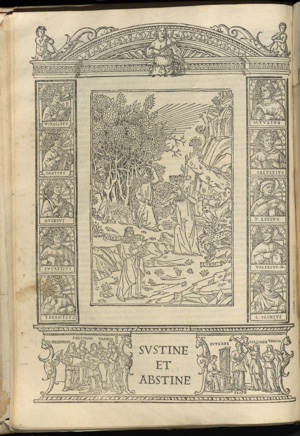

The design of the opening to Inferno in the 1529 edition—wherein Dante loses his way, is chased by a lion, a leopard and a she-wolf, and meets his guide, Virgil—shows key differences of approach by the publisher. Although the central woodcut is the same as that included in editions nearly forty years previous, it is here framed by a border that surrounds Dante’s scene with fictive portraits of Roman poets and historians. Below, the nine muses play a concert. Thus, any remnant of the Christian iconography of the 1491 and 1493 editions is replaced to instead place Dante on the level of these ancient writers—as he does himself in Inferno Canto 4 (see exhibition item). In the reserve area between the muses, printer Jacopo da Borgofranco has included the motto “SUSTINE ET ABSTINE” (which translates to “Bear and Forbear”), a saying of the Greek Stoic philosopher and former slave Epictetus about continuing forward despite adversity. This inclusion seems particularly appropriate, appearing as it does here at the harrowing outset of Dante’s arduous journey.