Dante from Manuscript to Printed Book

Vellutello Drawings and Editions

Introduction:

The three drawings attributed to Alessandro Vellutello (here on display for the first time outside the Morgan Library & Museum) along with related woodcut illustrations, allow us to follow the transition from images made to aid the thought process of a Dante scholar to those made with the reader in mind. As such, the resulting images stick closely, but with visual economy, to Dante’s text.

As convincingly asserted by Rhoda Eitel Porter in 2019,[1] the Morgan Library & Museum’s group of twenty Dante drawings were made by Vellutello in the perhaps two decades leading up to the publication of the 1544 Venice edition of the Divine Comedy that featured Vellutello’s new commentary. In general, Vellutello’s drawings include more fine detail and more components of the narrative than can be readily encompassed by the smaller format woodcuts in the edition. This necessitated editorial decisions made, no doubt, in concert with Vellutello, who seems to have maintained intensive oversight of the process.[2] As such, the 1544 edition stands as the first in which the commentary and the illustrations are designed to work in concert to aid the reader’s understanding of Dante’s poem.[3]

Attributed to Alessandro Vellutello

Italian, 1473–1515

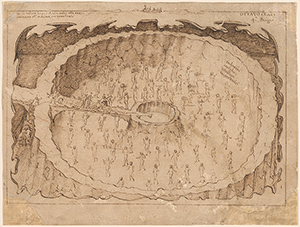

Inferno, Canto 20. The Circle of Soothsayers…

Pen and brown ink on paper

8 1/8 x 11 inches (20.7 x 28 cm)

Morgan Library & Museum

Gift of Mr. H.P. Kraus

(1 image)

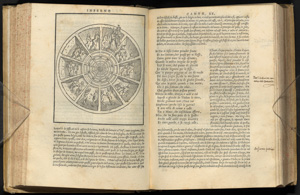

Attributed to Giovanni Britto

German, ca. 1500–after 1550, active in Venice

In Dante Alighieri

Inferno, Canto 20. The Circle of Soothsayers

in La comedia di Dante Alighieri con la nova

Espositione di Alessandro Vellutello…

Venice, 1544

Image: 5 x 4 1/4 inches (12.7 x 10.8 cm)

Cornell Library, Rare and Manuscript Collections

(1 image)

This pairing presents two different modes of envisioning the eighth circle of hell, known as Malebolge, devoted to the punishment of fraud, and described as a deep stone pit crisscrossed by paths and bridges (hyperlink footnote material to glossary section[4]).

Vellutello’s drawing for Inferno Canto 20 shows the fourth such bolgia—it is as if a lid has been lifted off to allow us to see inside. Virgil carries Dante to this place where purveyors of false prophecy, in an inversion of their efforts to see ahead, must walk backwards with their heads twisted all the way around (see also Michael Mazur, Inferno II: XX The Seers, from L’Inferno of Dante).

In Britto’s woodcut for the 1544 edition, the soothsayers contained in a circular composition with radiating stone ribs or buttresses, which emphasizes their eternal, retrograde procession. In his commentary on canto 20, Vellutello summarizes the presence and punishment of the soothsayers mentioning by name only Manto, daughter of the Theban seer Tiresias, who gave her name to Mantua, Virgil’s home city. Accordingly, Manto is the only identifiable denizen of hell in Britto’s woodcut: in Dante’s telling “she who covers up her breasts—which you can’t see—with her disheveled locks.”

Attributed to Alessandro Vellutello

Italian, 1473–1515

Purgatorio, Cantos 9–10: Section of the Mountain,

with Sun on the Right and Half Moon to the Left…

Pen and brown ink on paper

8 1/8 x 11 inches (20.7 x 28 cm)

Morgan Library & Museum

Gift of Mr. H.P. Kraus

(1 image)

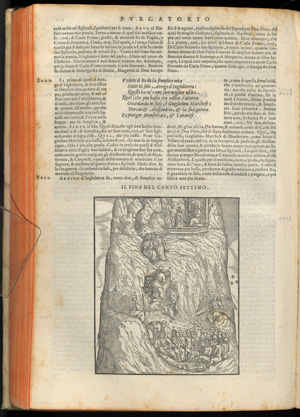

Attributed to Giovanni Britto

German, ca. 1500–after 1550, active in Venice

Purgatorio, Cantos 7-10: Dante and Virgil reach the Gate of Purgatory

in Dante Alighieri

Dante con l’espositione di Christoforo Landino…

Venice, Giovanni Battista and Marchi Sessa,

and brothers, 1564

Image: 5 1/8 x 4 1/8 inches (13.02 x 10.48 cm)

Cornell Library, Rare and Manuscript Collections

(1 image)

Vellutello’s drawing treating Purgatorio Cantos 9-10, in which the two pilgrims have completed their harrowing journey through Hell, shows Vellutello’s intense visual description of the pilgrims’ approach to the gate of Purgatory. He singles out its three steps symbolic of the sacrament of penitence: the first step white marble (contrition), then purple stone, split and cracked (confession), then blood-veined porphyry (satisfaction by works), capped by a last slab of adamant on which the gatekeeping angel waits.[5] This complexity is in line with Dante’s admission that he must redouble his efforts to be worthy of describing this new realm: “Thou seest well, Reader, that I rise to a higher theme; do not wonder, therefore, if I sustain it with a higher art.”[6] In his commentary, Vellutello reinforces this sentiment with the architecturally-oriented observation “the higher a building rises from the ground, the greater need to stabilize and reinforce it in its foundation.”[7]

By contrast, in the Venice 1544 edition based on the drawings, the woodcut artist packs a lot of Dante’s narrative into a single image, that includes aspects of cantos 7 through 10. In a hollow filled with souls (princes and rulers in life), one penitent raises clasped hands and leads the compline hymn “Te Lucis Ante Terminum (To Thee at Close of Day)” from Canto 8. While Dante sleeps, St. Lucy carries him to within sight of the door to Purgatory. At the top, the figure of the kneeling Dante, the encouraging Virgil, and the angel with the sword are compositionally very similar indeed to Vellutello’s drawing.

Attributed to Alessandro Vellutello

Italian, 1473–1515

Purgatorio, Cantos 10-12, The Purgation of Pride…

Pen and brown ink on paper

8 1/8 x 11 inches (20.7 x 28 cm)

Morgan Library & Museum

Gift of Mr. H.P. Kraus

(1 image)

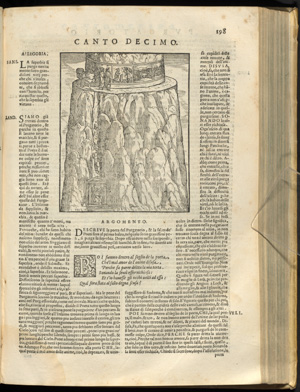

Attributed to Giovanni Britto

German, ca. 1500–after 1550, active in Venice

Purgatorio, Canto 10: Dante and Virgil reach the first Terrace of Purgatory

in Dante Alighieri

Dante con l’espositioni di Christoforo Landino…

Venice, Giovanni Battista and Giovanni

Bernardo Sessa, 1596

Image: 5 x 4 1/8 inches (12.7 x 10.48 cm)

Cornell Library, Rare and Manuscript Collections

(1 image)

Purgatorio Canto 10 finds Dante and Virgil’s reaching the first terrace of Purgatorio, where the prideful repent their offenses. As such, the travelers first encounter three marble relief carvings modeling personal humility (l. 28). Thus, we see Dante’s own view of the power of visual art to effect moral and spiritual redemption. Purgatorio Cantos 10-12 are a treasure trove of ekphrasis, or the verbal description of works of art, which Dante pointedly and playfully heightens by musing on the visual arts’ ability to fool the senses—a trope for praising the visual arts that has its roots in antiquity. Further, in his detailed drawing of the events of Canto 10, Vellutello experiments with representing Dante’s described works of art and their significance, marshaling the verbal and the visual to aid his readers’ understanding of the poem. As drawing moves to finished book illustration, it is also important to note that Dante’s visions “carved” (intagliato) upon the rock end up themselves once again as prints made from carved blocks of wood.

In his drawing, Vellutello labels the three relief carvings “three stories of humility sculpted in marble against excessive pride.” Dante and Virgil first encounter a relief carving of the ultimate expression of humility, that of the Virgin Mary’s submission to the angel Gabriel’s news that she will bear the Christ child. Next, King David sets aside his kingly mien to dance before the Ark of the Covenant. Here, Dante’s pilgrim pointedly observes that he can actually hear the singing of the seven celebrating choirs, and smell the incense. The influence of the art here in its stimulation of non-visual sensory experience is equal to the immersion of visions or dreams. The third and final story lpresents the selflessness the Roman Emperor Trajan—who halts his imperial procession to help a widow.

In both the drawing and the print, the penitent prideful are also seen arriving, the weight of their sins represented as heavy rocks that nearly crush their bearers’ backs (see also Sandow Birk, Purgatorio).

Footnotes

[1] Rhoda Eitel-Porter, “Drawings for the Woodcut Illustrations to Alessandro Vellutello’s 1544 Commentary on Dante’s Comedia,: Print Quarterly, vol. 36, March 2019, 3-16. ↩

[2] Eitel-Porter, 5. ↩

[3] Eitel-Porter, 7. ↩

made all of stone the color of crude iron,

as is the wall that makes its way around it.

Right in the middle of this evil field

is an abyss, a broad and yawning pit,

whose structure I shall tell in its due place.

The belt, then, that extends between the pit

and that hard, steep wall’s base is circular;

its bottom has been split into ten valleys.

Just as, where moat on moat surrounds a castle

in order to keep guard upon the walls,

the ground they occupy will form a pattern,

so did the valleys here form a design;

and as such fortresses have bridges running

right from their thresholds toward the outer bank,

so here, across the banks and ditches, ridges

ran from the base of that rock wall until

the pit that cuts them short and joins them all. ↩

[5] John D. Sinclair, trans, The Divine Comedy of Dante Alighieri, New York: Oxford University Press, 1961, vol. 2, 128-29. ↩

[6] Dante Alighieri, Purgatorio Canto 9, lines 70-72, translation John D. Sinclair. ↩

[7] Dante Alighieri, Alessandro Vellutello, and Donato Pirovano. 2006. La 'Comedia' di Dante Aligieri con la nova esposizione. Roma: Salerno, vol. 2, 886–887. Author’s translation. ↩