The Fame of Dante in Italy and Worldwide

Dante, Symbol of Italian Unity and Nationalism

In 19th century Italy, Dante became a symbol of national unity. The struggle for Italian unification was largely waged against the Austrian Empire, the hegemonic power in northern Italy, and against the Popes, who still ruled over Rome and the surrounding province. Italy finally attained independence in 1861; Venice was annexed in 1866 and Latium, including Rome, in 1870. The 600th anniversary of Dante’s death, in 1865, fell conveniently, only months after the transfer of the capital of Italy from Turin to Florence, and four years after the Risorgimento. The new king of Italy presided over a Dante festival which saw the inauguration of a statue on Piazza Santa Croce.

Still, some Italian-speaking regions remained under foreign rule, and Nationalists often enlisted Dante in their crusade to reintegrate them. In 1915, Italy declared war against Germany and Austria, in exchange for promised territories that included significant Italian populations.

L'Illustrazione Italiana, special issue on Dante

Milan, 1921, p. 38.

Cornell University Library, Rare and Manuscript Collections

(2 images)

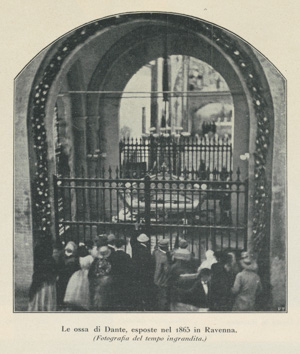

On the occasion of the 600th anniversary of Dante’s death, his “glorious bones” were displayed for the first time in 1865. The public fervor was so great that a new exhibition was organized in 1890 at the initiative of Francesco Bravi, director of the Liceo-Ginnasio (high school) Dante Alighieri of Ravenna. Bravi himself was an active member of the Second Socialist International, which shows that the “cult of Dante” transcended political affiliations and ideologies.

Stengel & Co.

Active Dresden, Germany, 1885–1945

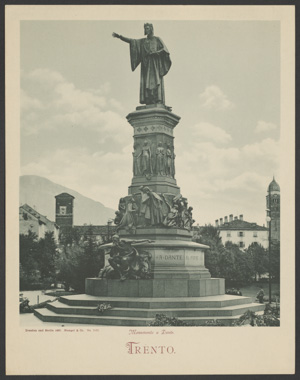

The Dante Monument in Trent by Cesare Zocchi

Berlin, 1897

10 x 8 3/4 inches ( 25.4 x 22.23 cm)

Cornell University Library, Rare and Manuscript Collections

(1 image)

After the Napoleonic Wars of the early 19th century, the bishopric of Trent was secularized and absorbed into the Austrian County of Tyrol. The Austro-Hungarian Empire governed it—an unacceptable situation for Italian nationalists. In 1896, the sculptor Cesare Zocchi, already the author of the monument to Garibaldi in Florence (1890), made a huge statue for Trento. It showed Dante as an exalted patriot, with his arm stretched out towards the Alps.

Various makers

World War I Italian Postcards

Image 1: 5 3/8 x 3 3/8 inches (13.5 x 8.5 cm)

Image 2: 5 3/8 x 3 1/2 inches (13.5 x 9 cm)

Image 3: 5 3/8 x 3 3/8 inches (13.5 x 8.5 cm)

Image 4: 5 1/2 x 3 1/2 inches (14 x 9 cm)

Image 5: 3 1/2 x 5 1/2 inches (9 x 14 cm)

Cornell University Library, Rare and Manuscript Collections

(5 images)

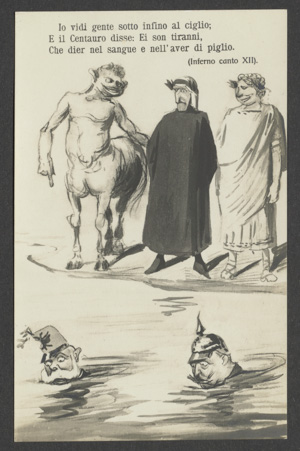

The first great war of the twentieth century showed the power of satire and caricature unleashed against the enemy along with guns and bombs.

On May 23, 1915, Italy declared war on Austria-Hungary and its allies (the German Reich and the Ottoman Empire), entering World War I on the side of Britain, France, and Russia, to regain control over a territory stretching from Trentino to Albania.

Dante appeared in many such caricatures, standing resolutely against Emperor Franz-Josef of Austria and the German Imperial eagle.