The Fame of Dante in Italy and Worldwide

Dante, Canonical Author

By the 16th century, it was a formality for the author of the first Italian grammar, Pietro Bembo, to assert Dante, Petrarch, and Boccaccio as the three most important authors in Italian. In 1554, Giorgio Vasari placed Dante at the center of his painting, Six Tuscan Poets—in the words of Adrastos Omissi, a “statement, painted to advertise Tuscan cultural supremacy in an Italy that was divided between a tapestry of polities and dialects.”

In parallel, more and more editions of the first biography of Dante, by Giovanni Boccaccio (1348) came with portraits of the author. While Boccaccio had described Dante with a dark complexion and a thick, curly beard, the “canonical” image of Dante that prevailed after the 16th century was different. Based on the death mask kept in Palazzo Vecchio (Florence), itself most likely based on a lost sculpture that used to be on his tomb in Ravenna, it showed a tall individual with a very austere, hairless and aquiline profile.

Unidentified artist

after Hieronymus Cock

Flemish, ca. 1510–1570

after Giorgio Vasari

Italian, 1511–1574

Portrait of Six Tuscan Poets

Engraving, ca. 1548–1570

15 x 8 inches (38.1 x 20.3 cm)

Cornell University Library, Rare and Manuscript Collections

(1 image)

The 1554 painting on which this engraving is based was commissioned by prominent Florentine patron Luca Martini from the Italian painter and art historian Giorgio Vasari. It creates an imaginary conversation among six literary figures who all hailed from the region of Tuscany, the cradle of the Italian Renaissance. The central figure, shown with his distinct, aquiline profile, is Dante Alighieri. Dante holds a book of Virgil’s poetry, to show his knowledge of Latin, and because Virgil serves as Dante’s faithful guide through the trials of his journey into hell. Petrarch, dressed in clerical garb and holding in his hand a copy of his own Scattered Rhymes, identifiable by the image of Laura on its cover, gestures toward Dante. Behind Dante at far left stands the poet Guido Cavalcanti (c. 1255-1300), seen pointing to the book in Dante’s hand, and Giovanni Boccaccio (1313-75), author of the Decameron but also Dante’s first biographer.

The remaining two figures are identified in the print as the Florentine scholars Angelo Poliziano and Marsilio Ficino, although the famous Dante commentator Cristoforo Landino has also been suggested as the figure on the far right. Any of these identifications would serve because of their associations with the Medici dynasty. Prints like this made possible the broad dissemination of such images of cultural supremacy of Tuscany.

Marcantonio Raimondi

Italian, ca. 1480–ca. 1534

After Raphael

Italian, 1483–1520

Apollo sitting on Parnassus surrounded by the muses and famous poets, ca. 1517–20

Engraving

14.3 × 18.8 inches (36.2 × 47.6 cm)

Acquired through the generosity of the Museum Advisory Council, in honor of Elizabeth Trapnell Rawlings and Hunter R. Rawlings III

Herbert F. Johnson Museum of Art, Cornell University

(1 image)

Through his printmaking workshop, Marcantonio helped Renaissance superstar artist Raphael to disseminate his designs during the first two decades of the sixteenth century. This engraving records an early drawing by Raphael for the Parnassus fresco in the Stanza della Segnatura in the Vatican.

Mount Parnassus is the home of the God Apollo and the nine muses (seen at center) and the seat of poetry and music in classical thought. In the finished fresco, Raphael included a host of recognizable poets—as Giorgio Vasari noted, just a few decades after the fresco’s 1511 completion: “all the most famous ancient and modern poets who ever lived or were still alive in Raphael's day.”[1] In this early conception, however, only Dante, Virgil, and Homer—seen in the upper left—are recognizable; several other laurel-crowned figures converse, but their identities are as yet unspecified. Thus, it is clear that Raphael felt Dante, Virgil, and Homer were clearly the logical starting points for this work commemorating literary greats, both ancient and modern.

Raphael’s composition in this sense also serves as a continuation of Dante’s Inferno, Canto 4, in which Dante and Virgil arrive in limbo and encounter the virtuous pagans. By including him in this scene, Raphael solidifies Dante’s legacy among the great poets. Marcantonio’s print ensured that Dante’s legacy was not limited to the few who could visit the Vatican’s inner sanctum.

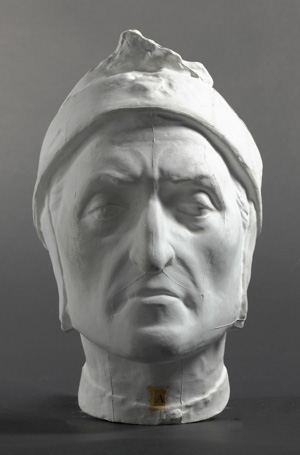

Unidentified artist

Italy, late 19th century

Death Mask of Dante

Plaster

12 x 6 1/2 inches (30.48 x 16.51 cm)

Cornell University Library, Rare and Manuscript Collections

(3 images)

Despite the unreliable record of Dante’s physical appearance, a desire to see, understand, and ultimately possess a likeness of the poet has ensured a market for versions both drawn and sculpted, including “death mask” casts like this one.

The only roughly contemporary description of what Dante looked like comes from his fellow poet Giovanni Boccaccio:

“Our poet was of moderate height…His face was long, his nose aquiline, and his eyes rather large than small. His jaws were large, and the lower lip protruded beyond the upper. His complexion was dark, his hair and beard thick, black, and curled, and his expression ever melancholy and thoughtful.”[2]

Dante with a beard? Nonetheless, the surviving so-called death masks of Dante accord largely with Boccaccio’s description and furnish a persistent image of the poet with aquiline nose, furrowed brow, downturned mouth, and jutting chin. These casts have attracted veneration since the late fifteenth century and exist in various forms—recast, modified, and photographed from previous models, for tourists, learned societies, and academic libraries in Europe and the United States including Cornell’s own (see “Some Dante Treasures Under Lock and Key” and “A Corner of the Dante Alcove”). For the Romantics like Thomas Carlyle, Dante’s visage as understood in his own day was the seat of Dante’s heroism as a poet, mingling contradictory emotions of tenderness, pride, and disdain for the pains he encountered and overcame in his lifetime.[3]

Giorgio Vasari credits Florentine sculptor Andrea Verrocchio (ca. 1435–1488) with the practice of making plaster casts, which led others to make death masks of loved ones, to place “over the fireplaces, doors, windows, and cornices of every home in Florence… so well made and lifelike that they seem alive.”[4] The survival of the death masks of Florentine luminaries like Lorenzo de’ Medici (1449—1492) serves as a bona fide example of this practice and would have spurred the desire to furnish such a likeness of Florence’s most famous son, even a hundred and fifty years after his death.

Fifteenth-century masks of Dante now in the Palazzo Vecchio, and the Bargello in Florence, purport to have been taken from sculpted tomb effigies or the dead poet’s own face, respectively. But scholars have pointed out the many discrepancies between typical death masks and these of Dante in which the muscles of his face and his eyelids seem instead activated by life.

Our cast, obtained by Willard Fiske in Italy during his travels, seems to trace its lineage most directly to an unattributed bronze bust portrait of Dante in the Capodimonte Museum in Naples (see fig. 1), which may also be the common model for other masks. Much of the proliferation of nineteenth century versions like this sprang from the publicity around the disinterment and measurement of Dante’s skeleton in Ravenna in 1865, the six-hundredth anniversary of his birth (see L'Illustrazione Italiana, special issue on Dante).

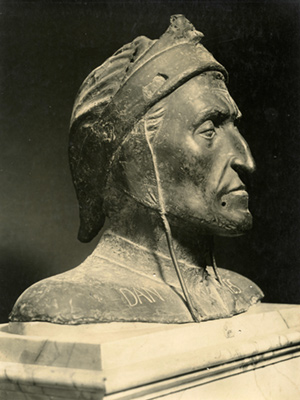

Fig. 1:Bust of Dante, bronze. Capodimonte Museum, Naples.

(1 image)

Giovanni Boccaccio

Italian, 1313–1375

Title page to the Biography of Dante

Rome, 1544

3.9 x 6.1 inches (10 x 15.5 cm)

Cornell University Library, Rare and Manuscript Collections

(1 image)

This is the first biography of Dante, published in the sixteenth century, here illustrated with a nineteenth century portrait of the poet.

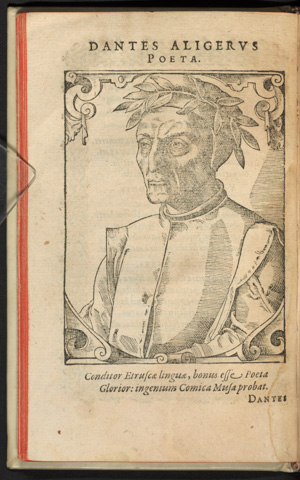

Tobias Stimmer

Swiss, 1539-1584

and Bernhard Jobin

German or Swiss, 1545–1593

Portrait of Dante in Nikolaus Reusner, Icones sive Imagines viuæ, literis clarorum virorum…(Icons or Living Images of famous men of letters…), second edition

Basel: Valdkirch, 1589

Image: 4 3/8 x 3 1/4 inches (11.11 x 8.26 cm)

Cornell University Library, Rare and Manuscript Collections

(2 images)

In his striking collection of ninety-nine chronologically arranged portraits of literati, the Silesian jurist and humanist Nikolaus Reusner included Dante. As the fourth figure, after Aristotle, Ptolemy, and Cicero, and just before Petrarch.

Footnotes

[1] Giorgio Vasari, The Lives of the Artists, translated and with an introduction by Julia Conway Bondanella and Peter Bondanella, Oxford University Press, 1991, 316. ↩

[2] James Robinson Smith, trans., The Earliest Lives of Dante, translated from the Italian of Giovanni Boccaccio and Lionardo Bruni, Aretino, New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1901, 42. ↩

[3] Jeremy Tambling, “Illustrating Accusation: Blake on Dante's “Commedia,” Studies in Romanticism, Fall, 1998, Vol. 37, No. 3, 407. ↩

[4] Giorgio Vasari, The Lives of the Artists, translated and with an introduction by Julia Conway Bondanella and Peter Bondanella, Oxford University Press, 1991, 239-40. ↩