Lafayette: Citizen of Two Worlds

Best known for his role in the American and French Revolutions, Marie Joseph Paul Yves Roch Gilbert du Motier de La Fayette (1757-1834) belongs to American and French history alike. His ideals were formed both by the French Enlightenment and his exposure to America’s culture of civic equality. As a result, he viewed himself as a “citizen of two worlds.” As early as 1792, in reference to the French Revolution of 1789, he boasted that he was an American citizen before there was such a thing as a French citizen. Lafayette’s contribution to the birth of the United States was formally recognized on July 22, 2002, when Congress conferred honorary citizenship on the hero “who gave aid to the United States in a time of need.” He is one of only six foreign citizens so recognized.

“Citizen of Two Worlds” illustrates Lafayette’s role in the American and French Revolutions, his lifelong advocacy of liberal ideals, and his support for reform causes such as the emancipation of African slaves. His personal and political relationships are explored through correspondence with his wife, other family members, and notable figures of the day such as George Washington and Thomas Jefferson.

The exhibition also investigates the origins and evolution of Lafayette’s mythic status as the defining symbol of friendship between France and the United States – a symbol solidified during his triumphal American tour of 1824-25, and amplified by Lafayette himself, who was a skillful manager of his own image. French and American officials have deployed his romanticized figure to promote understanding, forge new diplomatic or economic partnerships, or to curb hostility between the two nations ever since.

|

United States Congress. Message of Condolence to George Washington Lafayette and his Family, Signed by President Andrew Jackson, 1834. [zoom] | View/download a PDF of this item Lafayette’s death on May 20, 1834 occurred during a diplomatic crisis. France resented America for non-payment of debts dating from the War of Independence, while American merchants were laying claim to damages inflicted on their ships by French pirates. Tensions reached a peak in December 1832, when Jackson threatened to seize all French holdings in the United States. No wonder, then, that his condolences expressed no warm feelings towards Lafayette’s country. The historian Brian N. Morton observed that “America satisfied its debt to France by its glorification of one man”. |

|

Berenice Abbott, “Lafayette Park, Washington, D.C.”, ca. 1900. [zoom] This statue of Lafayette by the French sculptors Falguière and Mercié was erected in 1891 in the Nation’s capital. The pedestal features images of other notable French figures of the American Revolutionary War: Admirals de Grasse and d’Estaing, General Rochambeau, and military engineer Louis Lebèque Duportail. |

|

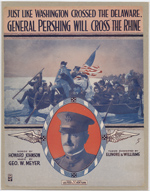

George Meyer and Howard Johnson. “Just like Washington...” Score for a Patriotic Song, 1918. [zoom] The United States entered World War I in 1917. Despite General Pershing’s fine rhetoric and Colonel Stanton’s rallying cry on the tomb of Lafayette, “Lafayette, we are here!” (on July 4), it was October before America could deploy nearly 200,000 “Sammies” to France, with 100,000 more landing each month. A “Lafayette Committee” founded in New York by prominent families such as the Astors and the Huntingtons sent 150,000 “La Fayette kits” (warm socks, a poncho, and writing material) to French soldiers as a token of appreciation for France’s support during the Revolutionary War. |

|

World War I Handkerchief, 1918. [zoom] Featuring images of Lafayette, Washington, Woodrow Wilson, and the Statue of Liberty, this handkerchief reflects the positive feelings that flowed between France and America at the end of World War I. Wilson, in particular, was very popular when he arrived at Versailles for the Peace Conference, advocating the creation of a League of Nations to avoid future wars. Yet his effort to moderate the victors’ claims was soon viewed as detrimental to French interests. France was also offended by the emphasis placed on French war debts. Expressing his frustration, French Premier Clemenceau (“The Tiger”) roared “When Colonel Stanton, arriving to join the fight, hastened to the graveyard of Picpus to utter his gallant salute to Lafayette, it was a sword he brandished in the sunlight, not a schedule of payment!” |

|

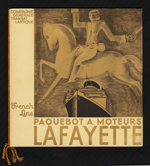

American Publicity Brochure for the Transatlantic Ocean Liner “Lafayette”, ca. 1930. [zoom] The Lafayette was the largest ocean liner in the French Line. When it arrived in New York for the first time in May 1930, six hundred New York City school children gathered to greet it, and a “Revolutionary” masquerade party was organized on board with Marquis Jacques de Dampierre, a descendant of Lafayette, as the master of ceremonies. The boat was destroyed by fire in 1938. |

|

Memorial Medal for the Centennial of Lafayette’s Death. May 1934. [zoom] | Additional images:

In a speech to Congress, Franklin D. Roosevelt said: “We cherish his memory more than that of any foreigner”. The New York Times also honored the occasion with fanfare on May 20, 1934, providing a full two-page portrait of the Marquis, and calling him “a perfect revolutionist. One may prefer the Lenin type as more up to date; the Lafayette type is still more cheerful.” |

|

La Victoire: Journal Français d’Amérique. New York, March 3, 1945. [zoom] Covering the progress of World War II for Francophone readers in America, La Victoire was published between 1942 and 1945 by Genevieve Tabouis, who was the niece of Jules Cambon (a former ambassador to the United States), and a close friend of Eleanor Roosevelt. Coverage in the left column reports on tensions between De Gaulle, the leader of the French Resistance in London, and Roosevelt. In the right column André Maurois, a respected figure in the French community exiled in New York, opportunely reminds readers of the good old days of the 18th century alliance. |

|

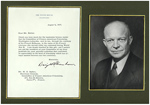

Letter from U.S. President Dwight D. Eisenhower to a “Committee of France-American Friendship”, August 9, 1957. [zoom] Acquired thanks to the generosity of Stanley Cohen in 2008. During World War II, 100,000 Free French soldiers fought under General Eisenhower’s command in Italy (1943). By the time of Operation Overlord and the Normandy invasion in June 1944, the “Free French Forces” numbered more than 400,000 (two-third of which came from the colonies); they played an important role in the liberation of Europe from Nazism. After the war, a group of French veterans sought to honor their former commander, whom General de Gaulle had already made a Compagnon de la Libération (a rare distinction given to 1,038 people only) in 1945. In his answer, Eisenhower evokes once again the coupe formed by Lafayette and Washington: “Thank you very much for the handsome bronze medal that the Committee of France-American Friendship, Washington-Lafayette, sent to me through the courtesy of the French Embassy, in the name of the French veterans who served under my command during World War II. I am deeply touched by this gift, and I assure you and the members of your Committee of my deep gratitude for your splendid activities that contribute so appreciably to the bond of friendship which has always existed between our two countries.” |

|

Nicolas Sarkozy. Testimony: France in the Twenty-First Century. New York: Pantheon Books, 2007. [zoom] | Additional images:

France’s newly elected president, Nicolas Sarkozy, published this political biography in 2006 in the months leading up to the French elections. In the preface of the American edition (May 2007), Sarkozy celebrates Lafayette as the ultimate symbol of the “unbreakable historical links” between France and America, whatever their disagreements. During a joint press conference with President Bush on August 11, 2007, Sarkozy pointed out that he was reading a biography of Lafayette. Subsequently, Republican Senator John McCain remarked that “Sarkozy is the first real pro-American I’ve met since Lafayette.” |