Raised In A World Of Privilege

Lafayette was born into a society of traditional communities held together by ideas of paternalism, patronage, and hierarchy. Before 1789, “Liberty” actually meant “law proper to a community.” The three French “estates” or “orders” were the clergy, the nobility (both privileged, if not always wealthy, minorities), and the Third Estate, or, the remaining 95 percent of the population made up of the urban bourgeoisie and the mostly rural masses. This status quo was maintained by the ruling King. Although limited by lax implementation and irregular application of its laws, France’s growing centralization fueled both resentment and greater expectations of the State, setting the stage for the Revolution of 1789.

During his youth, in the distant province of Auvergne, Lafayette led the life of a little king. When he left for Paris at age eleven, he was surprised that people did not take off their hats for him on the road. Like others of his class, although he was one of the richest bachelors in France, he was exempt from direct taxes. At the same time, according to the rules of his order, he was also prevented from engaging in business. But despite his privileged origins, he would spend his life in the service of liberal ideals. Lafayette advocated for one nation where subjects would be replaced by citizens, each of whom would enjoy - at least, theoretically - the same equal rights, duties, and opportunities.

|

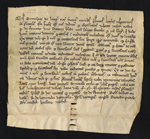

Medieval Record of Property, 1245. “Moulin de la Roche” [zoom]

Nos Bonuspar de Lang. notum facimus universis presentes litteras inspecturis tam presentibus quam futuris quod nos dedimus et concessimus dilecto militi nostro P. de Chavano duo sextaria bladi, unum scilicet frumenti et unum silig. quas habebamus ratione dominii et census in medietatem molendini quod dicitur de La Rocha quam tenet dictus P. a nobis et antecessores sui longo ipse tenuerunt…

This medieval property record, canceling a rent-in-kind due from Pierre de Chavaniac to his suzerain the landlord of Langeac, is the oldest document in Cornell’s Lafayette Collection. It shows that the Lafayette family had deep roots in Auvergne. When he acquired the Marquisate of Langeac in 1786, Lafayette inherited the feudal dues attached to a land where he did not live. Peasants were supposedly required to pay rent to use the lord’s mill, oven, wine press, or breeding stock. They were also levied death taxes, inheritance taxes and sale-of-property taxes. |

|

Ebenezer Mack. “Chateau de Chavaniac” in Life of Lafayette. Ithaca, New York: Mack, Andrus, & Woodruff, 1841. [zoom] Lafayette’s birthplace was a medieval castle “romantically situated” in central France, destroyed by fire and rebuilt in 1701. Inventories indicate that the family had a modest lifestyle. The estate was confiscated during the Revolution, and later returned to the family. In 1917, John Moffat, the son of the Scottish owner of an Australian coal mining empire, purchased Chavaniac and restored it. It is now a Lafayette museum, open to the public. |

|

Photographs of the Common Room and the Library in Chavaniac, Before and After Restoration. [From Hadelin Donnet, Chavaniac La Fayette, Le Manoir des Deux Mondes, Paris, 1990, Courtesy of Editions du Cherche-Midi] [zoom] | Additional images:

In 1916-1917, John Moffat, the son of the Scottish owner of an Australian coal mining empire, purchased Chavaniac with the decisive support of a private American foundation, and restored it. It is now a Lafayette museum, open to the public. |

|

Lafayette’s Parents: Christophe Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de La Fayette (1732-1759) and Julie de la Rivière (1737-1770). [zoom] | Additional images:

Originals held by the Herbert F. Johnson Museum of Art. The Marquis’ family could trace back its nobility as far as the 13th century, and counted among its members a marshal and the female author of La Princesse de Clèves (1678). Although Lafayette’s father lived in Auvergne and spoke the dialect of the local peasants or tarougne, he married very well: Julie’s father had an annual rent of 120,000 livres, or six times the pay of a vice-admiral, and a condominium in the Luxembourg Palace in Paris. Gilbert Jr. never knew his father, who died at war when he was two; his mother left Chavaniac for Paris soon thereafter, leaving her young son with two aunts, a grandmother, and a priest. She spent summers in Chavaniac. Here, she appears in an elegant “hiking outfit”, complete with a walking stick and a water jug around her waist. It probably refers to the famous Christian Pilgrimage to Compostela, which she perhaps accomplished: Le Puy, just south of Chavaniac, was a starting-point for one of the major pilgrim routes. In the region, Saint-Jacques pélerin was often confused with a great saint protector, St. Roch, usually depicted as a pilgrim with the famous coquilles saint-Jacques on his clothing, plus the dog who saved his life. Marie Joseph Paul Yves Roch Gilbert de la Fayette was actually christened in Saint-Roch de Chavaniac. |

|

Colonel Gilbert de La Fayette. Letter to His Sister Mlle du Motier. Minden (North Germany), July 16, 1759. [zoom]

“It was not exactly the intention, but it looks as if we were here for a promenade. The enemy is so far away that their presence is almost unnoticed. Let us hope they will cross the Weser... I believe [my wife] embarked on a frantic journey. I hope she will have fun... Please kiss my son for me”

Two weeks after Lafayette’s father wrote this letter, on August 1, the restless French abandoned their advantageous defensive position and crossed the Weser River. The British prevailed, and about 13,000 men were killed, easy-going Gilbert Sr. among them. His son would inherit a lifelong desire to avenge his father’s death by harassing Britain. |

|

The Iliad of Homer Translated by Alexander Pope. London, 1771. [zoom] This copy is from the library at Chavaniac. Lafayette received a classical education focusing on Latin, religious instruction, mathematics, military arts and equitation, first under the direction of priests at Chavaniac and later at exclusive institutions like the Collège du Plessis (an annex of the Sorbonne) and the Academy of Equestrian Arts in Versailles. His young imagination was stirred by stories of military feats in the works of Homer and Caesar. Although his knowledge of political philosophy was somewhat limited (Cornell has his copy of L'Histoire des deux Indes by l'Abbé Raynal [and Diderot], third edition of 1780), he was sympathetic to the Enlightenment and the reformist causes of the day. He also learned the rudiments of English, an uncommon accomplishment at a time when French was still the international language of the elite, and one that would prove fortuitous. During his first voyage to America, Lafayette would divide his time between studying military books and reading books in English. |

|

Abbé Guillaume Thomas François Raynal. Histoire Politique et Philosophique des établissements et du Commerce des Européens dans les deux Indes. Geneva, Pellet, 1780. [zoom] Cornell's copy is from Lafayette's collection. In the decade before the Revolution, Raynal (1731-1796) was perhaps the most celebrated of the Enlightenment philosophes then living. His massive history of European colonial and commercial expansion, with its attacks on slavery and its passionate support of the concept of national and popular sovereignty, was popular among the educated elite. Actually written by several authors (notably Diderot and tax-farmer Paulze), and first published in 1770, it went through more than forty editions in Raynal’s lifetime. Lafayette's copy is the revised text of 1780, usually characterized as the third edition. While previous editions offered a somewhat unflattering portrait of “the free men in English America,” (as feeble-bodied, feeble-minded degenerates) passages were rewritten after 1780 to put America in a much more favorable light. As Philippe Roger points out, this was partly due to Benjamin Franklin’s efforts. Franklin arrived in Paris in December 1776 to represent the rebel colonies. With his bonnet, his simple and affable manners, and his diplomatic skills (for example, he gave a dinner in his house in Passy with Raynal as guest of honor), le bonhomme Franklin became very popular. In the 1780 version, Franklin's scientific achievements were used as an example of the sort of prejudices that should be suppressed: “It took a Franklin to teach the physicians of our astonished continent to master lightning.” |

|

Lafayette. Letter to His Cousin Mlle de Chavaniac. February 8, 1772. [zoom]

“I have been particularly baffled by our neighbor’s latest catch in his forest [near Chavaniac]... the details would have amused me very much... The cousin’s marriage is broken off; there is another one on the carpet, but we have to lower our standards: Mlle de Roncherol, with five thousand paltry pounds a year, is a very disappointing let-down. The uncle consents to the marriage provided the Prince de Condé offers one of his regiments of cavalry... Mr. de La Vauguyon died, and was little regretted either by the court or by the town [Paris, as opposed to Versailles]. Thursday ball is postponed to the 15th...”

This is the oldest existing letter written by Lafayette. He jumps from one subject to another in a very witty, if cynical, fashion. Although he apparently had a knack for hunting and gossip, the young Musketeer did not enjoy the ghetto of Versailles; he preferred the military life and the tavern L’Épée de bois in the Latin Quarter. His chances of obtaining a position commensurate with his status were curtailed by the new reformist mood: the possibility of buying, selling or offering regiments of cavalry was abolished, his unit was disbanded and he was relegated to reserve status in June 1776. |

|

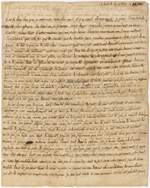

Lafayette. Letter to His Wife, Adrienne de Noailles de Lafayette. May-June, 1777. [zoom] Lafayette was nineteen-years old when he decided to join the American “insurgents.” He set off on his adventure with the knowledge and support of a wide variety of well-connected friends. He bought passage with his own money, plus additional contributions from linen manufacturers, the Van Robbais family (his travel companion De Kalb had married their daughter and niece), and from a former head of the royal spy agency. Powerful friends took an interest in his welfare. Writing to George Washington after Lafayette left Spain for America, Benjamin Franklin asked the American commander to look after “the boy.” Lafayette began writing this letter to his wife on board the ship “La Victoire” on May 30, 1777, and completed it at the house of a Mr. Huger in South Carolina on June 15:

[May 30th]: I am writing to you from a great distance, my dearest love... Your sorrow, that of my friends, Henriette [their first-born, who died during his journey], all rushed upon my thoughts... She is so delightful that she gave me the taste of little girls. Whatever the sex of our new baby, I shall welcome the birth with unbounded joy. [7th June] Whilst defending the liberty I adore, I will enjoy perfect freedom myself; I offer my service to that interesting republic from motives of the purest kind... Her happiness and my glory are my only incentives... The happiness of America is intimately connected with the happiness of all mankind; she will become the safe and respected asylum of virtue, integrity, tolerance, equality, and tranquil happiness... [15th June] I have arrived, my dearest love, in perfect health, at the house of an American officer... From Charlestown I shall repair to Philadelphia, to join the army.

|