Landscape and the Picturesque

The concept of the picturesque was among the most important aesthetic ideas of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Inspired by earlier European landscape art, it took shape in late eighteenth-century Britain, where it was popularized largely through the work of William Gilpin. A picturesque landscape occupied the middle ground between the awesome sublime—a roiling sea, impassable mountains—and the organized, pleasing beautiful—a formal garden, a country pasture. In numerous illustrated descriptions of his English countryside tours, Gilpin laid out the qualities of a picturesque scene, transposing ideas from French and Italian Romantic painting onto English ground. He prescribed rugged terrain, yet only in the middle to long distance; patterning, broken up by rough and irregular forms; and the suggestion of wildness and danger, carefully framed within a harmonious whole. In short, the picturesque presented nature as conceived by humans for perfect human enjoyment.

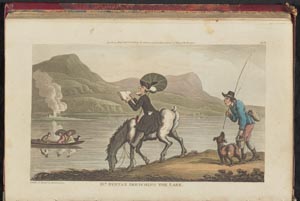

The silliness of certain aspects of the picturesque and its passionate followers were not lost on nineteenth-century publics. Jane Austen mocked it frequently in her novels, and William Combe lampooned it in his illustrated comic poem The Tour of Doctor Syntax in Search of the Picturesque, in which the protagonist’s quest for the ideal landscape is constantly derailed by tumbles into lakes or uncooperative farm animals. Yet its conventions, as well as those of the Romantic landscape art it drew from, remained deeply influential through the rest of the century, inflecting the way that land—even land whose features were utterly unlike those of Britain or Europe—was portrayed and popularly imagined.