North and South

Mass-produced nineteenth-century exploration photographs exist in a dizzying variety of forms, including the lantern slides, silver-based prints, ink-based photomechanical prints, and wood engravings modelled on photographic images that appear in this case. The format of a photographic image can reveal why it was made and how it was used. Format determined whether a picture was published with a book or journal, circulated individually, collected in an album, viewed alone or in a group, or even seen in two or three dimensions.

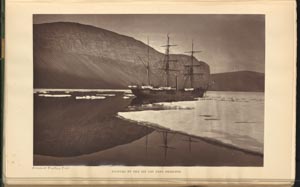

The items in this case indicate some of the ways that general and scholarly audiences learned about the Arctic and Antarctic. The photographs produced during the Challenger voyage appear in the fifty-volume report of the expedition’s findings as collotypes, a variety of photomechanical print well suited to the printing press, alongside more economical wood engravings and colorful chromolithographs. Photographs made during the British Arctic Expedition, led by George Nares, who had also led the Challenger expedition, appear in Nares’s account as wood engravings and woodburytypes, a variety of photomechanical print almost indistinguishable from photographs. They portray with frightening immediacy the icy wastelands that awaited Nares and his crew on their ill-fated voyage to reach the North Pole.

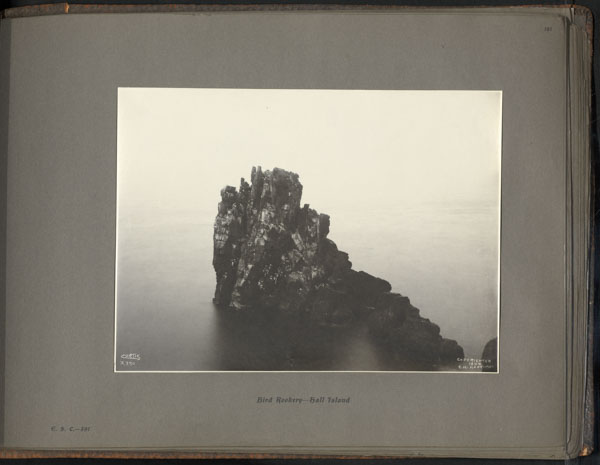

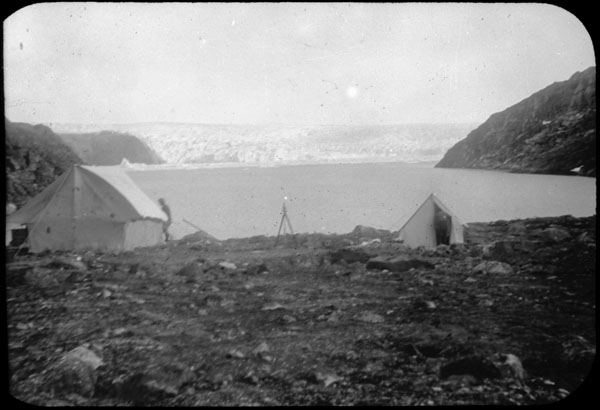

The superbly crafted photographs made by Edward Curtis for the Harriman Expedition were included in a souvenir album gifted to each of member of Harriman’s crew, including the Ithacan ornithologist and bird artist Louis Agassiz Fuertes. That Curtis copyrighted his images suggests a broader, commercial circulation for these images as well. The glacier photographs of the Cornell geologist Ralph Stockman Tarr became lecture slides, projected for students and colleagues for group visual analysis.