Mexico

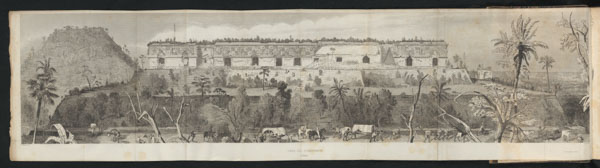

The first joint travelogue of the American writer John Lloyd Stephens and British artist Frederick Catherwood, Incidents of Travel in Central America, Chiapas, and Yucatan (1841), revealed an ancient civilization that few of their readers had heard of before. It recounted the travelers’ journey through regions of Central America and Mexico once dominated by the Maya, and where the staggering remnants of their civilization stood obscured by overgrowth, all but unknown to the wider world.

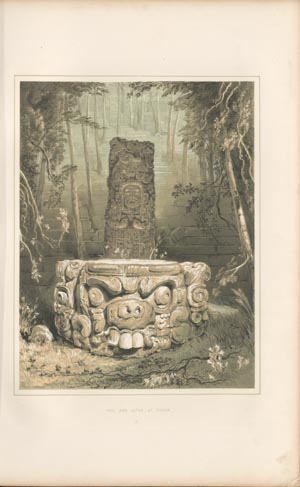

The wildly popular volume, written by Stephens and illustrated with wood engravings based on Catherwood’s drawings, was followed by another, Incidents of Travel in Yucatan (1843). It was based on a second journey of 1841–42. This time, Stephens and Catherwood brought along “a Daguerreotype apparatus, the best that could be procured in New-York.” The book contains lively accounts of Stephens’s and Catherwood’s successes and failures with the camera, which often either did not work at all or produced views deficient in various areas. Catherwood thus preferred to draw the monuments with a camera lucida, an optical tool that casts a traceable image of the artist’s subject upon the page. His Views of Ancient Monuments (1844), a book of lithographs based on his art work that appealed to the luxury rather than popular market, express both Catherwood’s preoccupation with exactness, which the camera lucida served well, and his particular style and vision.

The engravers preparing the illustrations for Incidents of Travel in Yucatan modelled their images on the travelers’ daguerreotypes and Catherwood’s drawings. But their earlier work, in which photography did not figure, was considered equally accurate and objective.

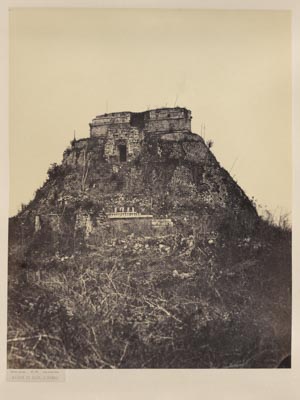

The best-selling travel books of the Mayanists John Lloyd Stephens and Frederick Catherwood inspired the French-born schoolteacher Desiré Charnay to become an explorer. He procured the sponsorship of France’s Minister of Public Instruction for his own archaeological expedition to Yucatan, and set out from Paris in 1857 with the cumbersome equipment necessary to make photographs. After three exhausting years of field work in Mexico, he assembled his prints into a huge folio for publication. Cités et ruines américaines: Milta, Palenqué, Izamal, Chichen-Itza, Uxmal, comprising the photographic folio displayed here and a volume of text, was published from 1862–63. Its appearance put photographs of Mayan monuments into the hands of scholars for the first time. Charnay’s account of his voyage and findings circulated amongst the general public as well. Smaller books in French and English, and an article in the popular travel journal Le tour du monde, presented his travels and findings alongside wood engravings, based either on the author’s words or photographs, at a greatly reduced cost.

In 1864, Charnay returned to Mexico in support of the doomed puppet regime established there by the French under Emperor Napoléon III. France’s general stance on expansion was actually ambivalent at this time, but Charnay stated his imperialist attitude toward Mexico plainly, writing that French control of the country would “assure our manufacturers outlets for their products and will pour into our hands the metallic treasures in which Mexico abounds.”