Greece

Like classical Rome, classical Greece loomed large in the education of young European gentlemen in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Yet Greece itself was not a typical travel destination until after the Second World War. Those who did make it there, according to John Murray’s 1853 travel guide, were “left alone with antiquity.” For almost everyone, that antiquity, the draw of the country, was viewed through book illustrations and photographs.

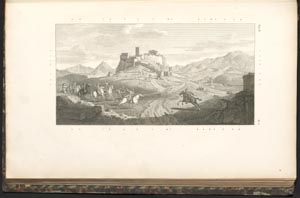

Enlightenment thinking proposed a crucial connection between archaeological study and the practice of art and architecture. “Artists who aim at perfection, must be more pleased and better instructed, the nearer they approach the Fountain-Head of their art,” wrote James Stuart and Nicholas Revett in their proposal for The Antiquities of Athens, which had appeared in its three-volume entirety in French as well as English by the early nineteenth century. With its precise measurements and appealing topographical views, the publication became a major influence on the Greek Revival style as it was employed, with great enthusiasm, in the United States beginning around 1820.

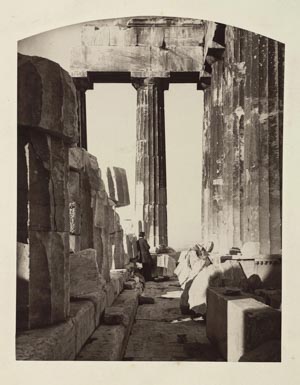

Study of Classical Greek architecture, and particularly the Athenean Acropolis, continued after Greece’s War of Independence (1821–30) and the decision subsequently made by the government to restore the site and “purify” it by removing the evidence of its use and alteration by later civilizations. The American photographer William Stillman, an associate of Cornell’s A.D. White and Willard Fiske, photographed the Acropolis as it was in 1869, exploring innovative viewpoints and image sequencing in an effort to create the impression of moving through the space.