Tradition of Courage

The creators of On Our Backs had a radical desire.

They envisioned a provocative and inspirational, widely distributed and glossy, raucously fun and liberatory sexual magazine for “the adventurous lesbian.” These West Coast feminists and transplants from Michigan and Minnesota were determined to realize something that hadn’t existed before. Their innovation built on foundations laid by queer and feminist people before them who had been bold enough to make original leaps in the same spirit, such as Edith Eyde who started Vice Versa, the first lesbian newsletter in the United States in 1947; the women who started the nationally distributed lesbian publication The Ladder in 1956; and multiple groups who had collected queer photo albums and correspondence and started community-run archives. The women involved in On Our Backs early on had strong connections with San Francisco Sex Information (SFSI), a group founded in 1972 by nurses to provide free, accurate, non-judgmental information about sex. They were inspired by the Boston Women’s Health Collective, who took knowledge about women’s bodies into their own hands and in 1970 published the first of what would be many editions of Our Bodies, Our Selves. The women who created On Our Backs marshaled courage as had queer bibliophiles and archivists, sex educators, and feminists before them.

Queer bibliophiles

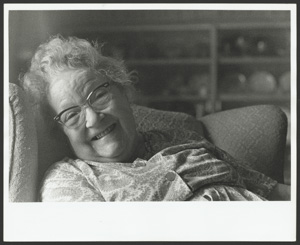

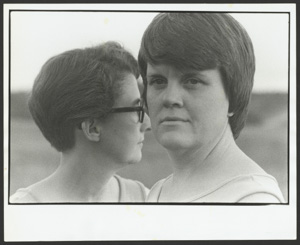

On Our Backs photographer and writer Honey Lee Cottrell also created portraits of lesbian literary groundbreakers, including Jeannette Howard Foster, Barbara Grier, Donna McBride, Valerie Taylor, and Barbara Gittings. Shown here are her portraits of the first three.

Honey Lee Cottrell. [Jeannette Foster], late 1970s.

Gelatin silver print

Honey Lee Cottrell papers

Collection/Call #: 7822

Box: 5 | Folder: gray binder

(1 image)

Honey Lee Cottrell. [Barbara Grier and Donna McBride], late 1970s.

Gelatin silver print

Honey Lee Cottrell papers

Collection/Call #: 7822

Box: 5 | Folder: black binder

(1 image)

Foster (1895-1981) withdrew from the University of Chicago in 1914 when she realized that she loved another woman, and this “triggered her lifelong search in professional literature and belles lettres for an understanding of female homosexuality.” Foster returned to university and earned undergraduate degrees in chemistry and library science and a Ph.D. in literature. In 1948, she started work as the first librarian of Dr. Alfred Kinsey’s Institute for Sex Research, and in 1956 published the first critical study of lesbian literature, Sex Variant Women in Literature: A Historical and Quantitative Survey. She influenced generations of queer bibliophiles, including her friend, novelist Valerie Taylor; Barbara Gittings, who started the Task Force on Gay Liberation within the American Library Association; and Joseph Gregg, who became the founding librarian of Chicago’s Gerber/Hart Library and Archives.

At the first Lesbian Writers Conference in Chicago in 1974, keynote speaker Barbara Grier (1933-2011) acknowledged her indebtedness to Foster. In 1973, Grier and her lifelong partner Donna McBride (1932- ), along with another couple, Anyda Marchant and Muriel Crawford, founded Naiad Press to publish literature with lesbian themes. Upon Grier’s death, author Katherine V. Forrest described her accomplishments as “just monumental, given the obstacles she faced. There was such virulent homophobia. Barbara was nothing if not fearless.”[1]

Feminism

In 1970, the first issue of off our backs proclaimed it was a newspaper for “all women who are fighting for the liberation of their lives.” With a focus on entrenched global inequities for women in wages, opportunities, laws, and control of their bodies, off our backs highlighted coercive and damaging aspects of sexuality that harmed women. The first issue opined: “Through the sexual ‘revolution’ we have been cast in the role of sexual object, pleasure machines to be victimized by unsafe and unresearched birth control.”

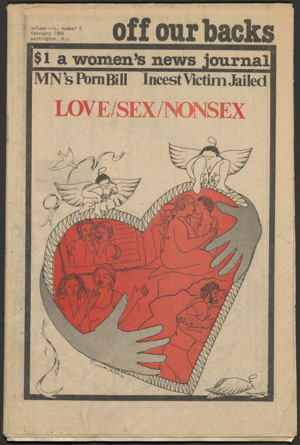

Fourteen years later, the February 1984 off our backs contrasts a romantic Valentines-themed graphic with headlines about the Minnesota anti-pornography law and news of an incest victim. off our backs was widely read in the lesbian community and took Andrea Dworkin and Catharine MacKinnon’s position that pornography was itself violence against women and perpetrated more violence. The off our backs writers concentrated on women’s mistreatment and loss of agency in sex and condemned the lesbian artists and activists creating new sex-positive art for betraying correct feminist values.

off our backs, vol. XIV no. 2, February 1984. Cover illustration by Jean Vallon.

Collection/Call #: Human Sexuality HQ1101 .O32

Box: 1

(1 image)

Debi Sundahl, Nan Kinney, Myrna Elana, and Susie Bright would have seen this “LOVE/SEX/NONSEX” issue of off our backs for sale when they were putting the finishing touches on the first issue of On Our Backs. They each experienced the problems off our backs reported on: discrimination, misogynistic stereotypes that limited women’s opportunities, and the impact of sexual violence. However, their approach was to fight for more space for women’s pleasurable sexuality. In her notes, Sundahl wrote: “Sure, pornography is sexist. Sexism invades every part of our lives, and [the] porn industry and our sexual relations are no exception, but does that mean we ban it? No. We seek changes, just as women have sought for change in their economic and social lives.”[2]

On Our Backs was a whole new kind of feminist publication, one that invited and celebrated a vast range of lesbian erotic expression. It welcomed debate and humor too, and celebrated community power. A strong vein of satire animated On Our Backs’ exploration of politics, art, and sexuality. The title of the magazine deliberately poked fun at the prudery of off our backs. Susie Bright recalls, “The idea was that sex has the ironic ability to turn conventional roles upside down— one can be 'on your back’ physically and yet ‘running the show’ in an erotic situation. Top is not always top and bottom is not always bottom.”

Women’s sexual empowerment

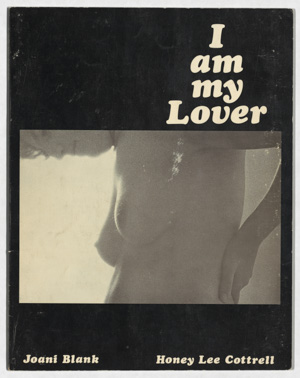

In 1978, Joani Blank was ready to publish I am my lover, a photographic celebration of women giving themselves sexual pleasure, created by her and photographers Honey Lee Cottrell and Tee Corinne. Though Blank had created her own company, Down There Press, the women still faced the obstacle of finding a printer. Unable to secure a printer in the United States, they found one in Mexico who agreed to do the job. However, the printer did not return the original photographs, so the first edition could not be re-printed. This is one of only six copies of the first edition held in U.S. libraries.

Joani Blank and Honey Lee Cottrell with Tee Corinne, I Am My Lover (Burlingame, CA: Down There Press, 1978).

Collection/Call #: Human Sexuality HQ46 .I2 1978

Box: Aeon TN 119570

(3 images)

For the second edition nineteen years later, Blank needed all new photographs. Phyllis Christopher provided them.

San Francisco Pride

The San Francisco Gay Liberation Front organized events to mark the first anniversary of New York City’s 1969 Stonewall Rebellion against the police’s brutal treatment of LGBT people. Police officers on horseback and motorcycles raided the June 28, 1970 gathering in San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park. The annual events have grown tremendously since then. Now organized by the San Francisco Lesbian Gay Bisexual Transgender Pride Celebration Committee, the event's mission is “to educate the world, commemorate our heritage, celebrate our culture, and liberate our people.”

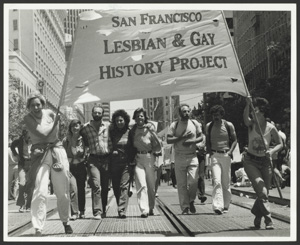

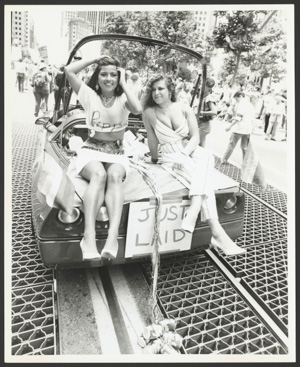

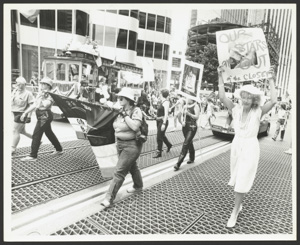

These three photographs of San Francisco Pride parades in the 1980s show the On Our Backs and San Francisco Lesbian & Gay History Project contingents. The History Project paved the way for the GLBT Historical Society and its museum.

Honey Lee Cottrell. [San Francisco Lesbian & Gay History Project contingent in a San Francisco Pride Parade.] early 1980s.

Gelatin silver print

Honey Lee Cottrell papers

Collection/Call #: 7822

Box: 5 | Folder: gray binder

(1 image)

Honey Lee Cottrell. [Two On Our Backs models in a San Francisco Pride parade, riding a car decorated “Just Laid.”] 1985-86

Gelatin silver print

Susie Bright papers and On Our Backs records

Collection/Call #: 7788

Box: 13 | Folder: 141

(1 image)

Honey Lee Cottrell. [The On Our Backs contingent walking in a San Francisco Pride parade, Debi Sundahl carrying a sign “Our Stars are Out of the Closet.”] 1985-86.

Gelatin silver print

Susie Bright papers and On Our Backs records

Collection/Call #: 7788

Box: 13 | Folder: 141

(1 image)

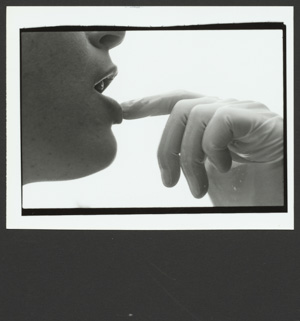

Sexy lesbian safer sex

In the 1970s, lesbian, gay, and feminist groups created their own health guides to overcome persistent barriers to obtaining respectful medical treatment. Facing the onslaught of AIDS in the 1980s, California activists produced public health campaigns that encouraged safer sexual practices by making them look sexy. Erotic images distinguished California activists’ public health campaigns for safer sex. In that spirit, these photographs by Honey Lee Cottrell eroticize and bring an artist’s eye to using latex dental dams and gloves. Lesbian AIDS activists suggested using these medical supplies to create barriers between mouths, genitals, and hands as methods for safer sex. Susie Bright is the model.

Honey Lee Cottrell. [Latex glove]. Model: Susie Bright. Published in On Our Backs, 1987.

Gelatin silver print

Honey Lee Cottrell papers

Collection/Call #: 7822

Box: 2 | Folder: 25

(1 image)

Honey Lee Cottrell. [Latex dental dam]. Model: Susie Bright. Published in On Our Backs, 1987.

Gelatin silver print

Honey Lee Cottrell papers

Collection/Call #: 7822

Box: 2 | Folder: 25

(1 image)

Footnotes

[1] https://www.chicagotribune.com/news/obituaries/la-me-barbara-grier-20111113-story.html ↩

[2] Draft notes. Debi Sundahl. Circa 1985. 7788. Box 23, Folder 25. ↩