Scared Straight: Fables and Cautionary Tales

From its inception, children’s literature was used to promote good behavior in young readers -- either by modeling the values that adults wanted children to emulate, or by showing the dire consequences of undesirable actions. Authors and illustrators did not shy away from depicting graphic violence and death to get the point across. After all, the child’s soul was at stake. With some estimates of European child mortality rates as high as 30% for the 16th-18th centuries, every child needed to be prepared to die with a clear conscience, or risk eternal damnation.

|

Æsop’s Fables; retold, illustrated with woodcuts, and printed by Elfriede Abbe. Ithaca, N.Y., 1950. No. 216 of 500 copies printed. [zoom] Fables are short stories featuring anthropomorphized animals, with a blatant moral. For millennia, the fables attributed to a mysterious Greek slave named Aesop have been used to instruct adults and children in cultures across the globe. |

|

Carlo Collodi. Pinocchio. Illustrated by Sarah Fanelli. Cambridge, Mass.: Candlewick Press, 2003. [zoom] Additional images:

Written in installments for an Italian children’s magazine, Collodi’s original fairy tale about a willful, selfish puppet who must learn to behave responsibly before he can become a real boy depicts a far darker journey than the one portrayed in the Disney film. Pinocchio kills the wise talking cricket, the blue-haired fairy dies TWICE, and the puppet himself survives a hanging and imprisonment in addition to being swindled by con artists, becoming a donkey, and being swallowed by a whale. |

|

Wilhelm Busch. Max und Moritz: eine Bubengeschichte in sieben Streichen. München: Braun und Schneider, ca. 1930. [zoom] |

|

Max and Moritz wooden push puppets. Germany, 20th century. [zoom] The two young stars of this German classic (first published in 1865 by the “Father of the Comic Strip,” Wilhelm Busch) play a series of pranks on their neighbors: killing and stealing the widow’s chickens, putting gunpowder in the teacher’s pipe, etc. But then they get their comeuppance: they are ground into pieces at the sawmill and fed to the ducks. |

|

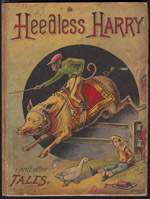

Heedless Harry and Other Tales. New York: McLoughlin Bros., ca. 1890. [zoom] Additional images:

In this Americanized Struwwelpeter, children suffer horribly for their disobedience: the boy who is too picky about his food starves to death, and a girl sucks her fingers down to nubs. |

|

Beatrix Potter. Autographed letter. July 13, 1943. [zoom] Additional images:

In this letter to a fellow writer, Beatrix Potter (1866-1943) describes the sort of books she liked as a girl: “silly stories about other little girls’ doings.” She vividly recalls a scene in Little Sunshine’s Holiday (Dinah Craik, 1871) of a girl being rewarded at the end of a journey with a “basin of cream with a large spoonful of strawberry jam floating on it” – a treat that calls to mind the berries and milk that Peter Rabbit’s well-behaved siblings receive. |

|

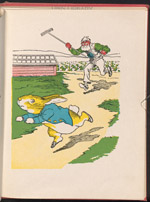

Beatrix Potter. The Tale of Peter Rabbit. Chicago: M.A. Donohue & Co., ca. early 1900s. [zoom] Peter’s near escape from becoming Mr. McGregor’s rabbit pie serves as a warning to always obey your mother in this famous English story. |

|

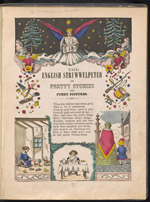

Heinrich Hoffmann. The English Struwwelpeter, or, Pretty Stories and Funny Pictures for Little Children. Bloomsbury, England: W. Mogg, ca. 1860. [zoom] Additional images:

Hoffmann, a German physician, wrote this collection of poems for his own child. Most of the poems feature a misbehaving child who suffers a drastic consequence. The girl who plays with matches sets herself on fire; the boy who sucks his thumbs loses them to a tailor with a giant pair of scissors. |