Birds and Bees: Sex and Puberty

The earliest versions of the fairy tales popularized by Perrault and the Grimms were not shy about sex. Red Riding Hood takes off her clothes and hops in bed with the wolf, and Sleeping Beauty gets knocked up before she’s woken up. But somewhere between the Puritans and the Victorians, people started to worry that if a child reads about sex, that child might be more likely to have sex before marriage, or with the wrong person, or (gasp!) for pleasure instead of procreation. In the U.S., this attitude prevailed until the First World War. At that point, so many soldiers came back with syphilis and gonorrhea that sex education suddenly became a public health issue, rather than a purely moral one. But the question of how much exposure to sex in books and other media is appropriate for children and teens is one that parents, educators and politicians are still trying to answer.

|

Sylvanus Stall. What a Young Boy Ought to Know. Philadelphia: Vir, 1909. [zoom] Stall was a Lutheran pastor, and his popular series of published sex-ed sermons (also recorded and sold on Edison wax cylinders – the first audio books!) reflected the Victorian mindset. His primary concern is preventing masturbation, which he claimed would lead to all kinds of horrors: moral depravity, insanity, physical decrepitude, and death, to name a few. |

|

Frances Strain. Being Born. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts, ca. 1954. [zoom] The mid-20th century saw a recognition of the need for sex education of a more direct nature. Strain’s book makes a valiant effort at accurately describing the human reproductive system, complete with microscopic photos… but also claims that there is no reason for women to feel discomfort during menstruation as long as they stay warm and keep a positive attitude. |

|

Alex Comfort. The Facts of Love: Living, Loving, and Growing Up. New York: Crown Publishers, ca. 1979. [zoom] Sex-ed takes a different approach after the sexual revolution of the 1960s, with a growing recognition that since teens are going to have sex anyway, they might as well be as informed as possible. There is also more acknowledgement – and acceptance – of previous taboos, like birth control, homosexuality and masturbation. |

|

Peter Mayle. Where Did I Come From? : The Facts of Life Without Any Nonsense and With Illustrations. Illustrated by Arthur Robins. Designed by Paul Walter. Secaucus, N.J.: Lyle Stuart, 1973. [zoom] Additional images:

The question of how and when to explain sex to children received some bold answers in the post-sexual-revolution 1970s. Mayle’s controversial book, aimed at early elementary-aged children, includes graphic illustrations of naked adults, and even tries to describe how sex feels: “like scratching an itch, but a lot nicer.” |

|

Robie H. Harris. It’s Perfectly Normal : A Book About Changing Bodies, Growing Up, Sex, and Sexual Health. Illustrated by Michael Emberley. Cambridge, Mass.: Candlewick Press, ca. 1994. [zoom] Harris’s candid and kid-friendly explanations of all things sexual won several awards from literature critics, and is still considered a benchmark in the sex-ed genre. Yet the book continues to be challenged by adults who object to the portrayal of masturbation, fornication, homosexuality, and a host of other sexual behaviors as “perfectly normal.” |

|

Nancy Garden. Annie On My Mind. New York: Farrar, Straus, Giroux, 1984. [zoom] Gay characters had been appearing occasionally in teen literature since 1969, but Garden’s 1982 novel was the first to put a teenage lesbian couple front-and-center. It was also revolutionary in allowing Liza and Annie to weather the controversy surrounding their relationship and ultimately decide to continue it into adulthood. |

|

Justin Richardson. And Tango Makes Three. Illustrated by Henry Cole. New York: Simon & Schuster Books for Young Readers, 2005. [zoom] Based on the true story of two male penguins who paired up and hatched a foster chick in the Central Park Zoo, this charming picture book has come under fire from conservatives for presenting such a natural and positive example of homosexual parenthood. |

|

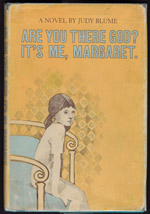

Judy Blume. Are You There God? It’s Me, Margaret. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Bradbury Press, 1970. [zoom] The eleven-year-old heroine of Blume’s immensely popular novel has been embraced by generations of tween-agers, who can relate to Margaret’s preoccupation with breast development, menstruation, and boys. It has been reviled by many adults for the very same reasons – as well as for Margaret’s open questioning of organized religion. |

|

Beatrice Sparks, editor. Go Ask Alice. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall, 1971. [zoom] This seminal cautionary tale against the free-wheeling counter-culture of the late ‘60s-early ‘70s purported to be the actual diary of a teen overdose victim, but was later admitted to be largely fictional, based on several of Sparks’ therapy patients. It offers up every possible example of a negative sexual experience – molestation, rape, prostitution, unwanted pregnancy – as a warning against the consequences of drug abuse. |