The Gettysburg Address

Gettysburg, November 1863

Abraham Lincoln composed his Gettysburg Address for delivery at the public ceremony dedicating the Soldiers’ National Cemetery at Gettysburg on November 19, 1863. A solemn program of poems, hymns, lectures, and music was planned, and Lincoln was invited to contribute some appropriate remarks. With the nation still mourning the Gettysburg dead, immense crowds were expected to attend the consecration of the cemetery grounds, where laborers were still in the process of burying the fallen soldiers. The President left Washington on November 18 with much of the draft of his speech complete. He spent the night at the home of Gettysburg attorney David Wills, where he is believed to have finished the final draft.

Edward Everett, a noted orator and former U.S. Senator, was invited to deliver the principal speech. Everett undertook his assignment with serious dedication, preparing a sweeping narrative that ranged from the funeral customs of Athens, to the purpose of war, to a detailed, day-by-day account of the Gettysburg battle. His oration lasted two hours. Lincoln’s two-minute Address followed.

Reactions to Lincoln’s Address the following day were mixed, with reviews in the press falling along partisan lines. Some newspapers neglected to report on Lincoln’s speech altogether, favoring extracts from Everett’s oration instead. While many did remark on the beauty and eloquence of Lincoln’s words that November day, a generation would pass before the majority of the American public came to celebrate the Gettysburg Address as one of the greatest speeches in American history.

Late in the [nineteenth] century, Americans would rediscover Lincoln’s remarks...call them by the name we still know, and find the meaning of their country there. In the twenty-first century, Americans are still saying this is who we are—

Gabor Boritt, The Gettysburg Gospel

|

Thomas Hewlings Stockton. Prayer at the Dedication of the National Cemetery at Gettysburg, Thursday, November 19th, 1863. Philadelphia: W.S. & A. Martien, 1863. [zoom] Reverend Thomas H. Stockton, Chaplain of the House of Representatives, offered the opening prayer at the Gettysburg dedication ceremony. |

|

Edward Everett. An Oration Delivered on the Battlefield of Gettysburg... New York: Baker & Godwin, 1863. [zoom] | [read this book] Copy with original paper covers. Everett took an active role in the dissemination of his speech both before and after its delivery. He took care that the press had copies in advance, something Lincoln did not have time to do for his own Address. In this edition of Everett’s Oration, Lincoln’s Address appears on page 40, but it is not mentioned on the title page. Gift of Andrew Dickson White |

|

Edward Everett. An Oration Delivered on the Battlefield of Gettysburg... New York: Baker & Godwin, 1863. [zoom] | Additional images:

Bound copy, with Edward Everett’s bookplate. Everett ordered some copies of his Oration specially bound in cloth for presentation to friends and dignitaries. This copy contains Everett’s own bookplate. |

|

Edward Everett. Engraving. From the Original Painting by Alonzo Chappel. New York: Johnson Fry & Co., 1863. [zoom] Susan H. Douglas Collection of Political Americana |

|

The Gettysburg Address. In The New York Times, November 20, 1863. [zoom] On the day after the dedication at the National Cemetery, The New York Times printed the Gettysburg Address on its front page, along with a report on the ceremony. Gift of Nicholas H. and Marguerite Lilly Noyes |

View an image of this exhibition case: 1

The Gettysburg Address Manuscripts

The President wrote five copies of his Gettysburg Address. The first and second drafts—owned since 1916 by the Library of Congress—remain a source of disagreement among scholars. Some believe the second draft was the copy from which Lincoln read at Gettysburg. Others point to differences between the second draft and Lincoln’s spoken text as recorded by reporters present, along with other inconsistencies. Most agree, however, that at least one of the copies, and maybe both, were made before Lincoln gave the speech, and that the second draft could have been the copy from which Lincoln read.

Lincoln made three additional copies for charitable purposes after the Gettysburg dedication. He wrote the first of these at the request of Edward Everett, who sought to raise money for soldiers by selling the manuscript at the New York Sanitary Fair. The speech did not sell at the Fair, but would later pass privately through several hands until it was sold in 1929 to Chicago banker James C. Ames for $150,000. Upon Ames’ death in 1943, his heirs offered it to the Illinois State Historical Library for $60,000. Illinois school children raised funds for its acquisition with help from Marshall Fields. Today the “Everett Copy” remains in Springfield, Illinois as part of the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library.

The fourth and fifth copies were made at the request of the historian George Bancroft and his stepson Alexander Bliss to raise funds for the Baltimore Sanitary Fair. When Bancroft discovered that the first manuscript Lincoln sent was not well-suited for making lithographic reproductions, Bliss asked for a new copy, which the President obligingly made, allowing Bancroft to keep the unsuitable copy. This fourth copy, now known as the “Bancroft Copy,” was bequeathed to Wilder E. Bancroft, Professor of Chemistry at Cornell, who sold it in 1929 to dealer Thomas Madigan for $90,000 - $100,000. As the Depression worsened, however, Madigan was unable to recoup his investment. He sold the document to the Nicholas H. Noyes family in 1935 for $50,000, and the family gave it to Cornell in 1949.

|

Alexander Bliss. Autograph Leaves of Our Country’s Authors. Baltimore: Cushings & Bailey, 1864. [zoom] | Additional images:

The fifth copy of the Gettysburg Address—the “Bliss Copy”—was used to make a lithographic reproduction that appeared in Autograph Leaves of Our Country’s Authors, a handsome book of autographs by famous writers sold to raise money for Union soldiers at the Baltimore Sanitary Fair. The original manuscript remained in the Bliss family until 1949, when it was sold at auction for $54,000. The “Bliss Copy” is the only copy of the five manuscripts to include a formal title and Lincoln’s signature. |

|

The Unique and Final Holograph Manuscript of Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address... New York, Parke-Bernet Galleries, April 27, 1949. [zoom] This catalog documents the sale of the “Bliss Copy” of the Gettysburg Address, the only one of the five copies Lincoln wrote that would change hands at a public auction. It sold to Cuban businessman Oscar Cintas for $54,000. Cintas, a former Cuban ambassador to the United States, left the manuscript to the American people by bequest. It arrived at the White House in 1959, and it remains in the Lincoln bedroom there today. An informed observer at the sale annotated this copy of the auction catalog: “Bids opened at $25,000 (by Kirschenbaum for Carnegie & Sessler). Lafayette College bid $51,000. The under bidder (at $53,000) was David Kirschenbaum [of Carnegie Book Shop].” |

|

Photograph of Cornell President Edmund Ezra Day with Cornell’s copy of the Gettysburg Address [Cornell University, Ithaca, N.Y., ca. 1949]. [zoom] Cornell’s manuscript copy of the Gettysburg Address arrived on campus in 1949, the gift of Nicholas H. and Marguerite Lilly Noyes. It is the only copy to be accompanied by a letter of transmittal signed by Lincoln, along with the franked envelope in which the manuscript was originally delivered to George Bancroft. Between 1916 and 1959, all five of Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address manuscripts made their way from the hands of private individuals into institutional collections. |

|

Abraham Lincoln. The Gettysburg Address. February 29, 1864. [zoom] | Additional images:

Cornell University Library’s copy of Abraham Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address is one of five known copies in Lincoln's hand, and the only copy owned by a private institution. The four other copies are owned by public institutions: two at the Library of Congress, one at the Illinois State Lincoln Presidential Library, and one in the Lincoln Bedroom at the White House. |

|

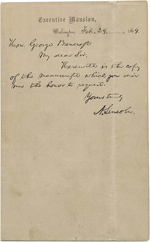

Abraham Lincoln. Autograph Letter to George Bancroft. Washington D.C. February 29, 1864. [zoom] | Additional images:

Cornell University Library’s copy of the Gettysburg Address is the only one of the five copies to be accompanied by a letter from Lincoln transmitting the manuscript and by the original envelope addressed and franked by Lincoln. Hon. George Bancroft Yours Truly |

View an image of this exhibition case: 1

The Myths of Gettysburg

You may have heard that Lincoln wrote the Gettysburg Address in great haste – dashing it off on the back of an envelope while riding on the train from Washington to Gettysburg.

While historians have long known this story to be untrue, the tale is remarkably persistent. How did this tale come to lodge so stubbornly in the minds of so many Americans? The longevity of this fiction can be attributed in large part to the work of Mary Shipman Andrews and her book The Perfect Tribute. First published in 1906, the book was a best seller that appeared in multiple editions throughout the first half of the twentieth century. It was assigned reading for generations of schoolchildren.