Back to the Earth: Coral Reefs and Earthworms

As a young man, Darwin was interested primarily in geology. He returned to geological pursuits near the end of his life, first by substantially revising his 1842 book on coral reefs.

Darwin also returned to his curiosity about the relationship of earthworms and soil structure. Forty years earlier he had published two papers on the formation of “vegetable mould” by earthworms. Eliciting the help of some of his sons, a Wedgwood niece, and several others, he revived these investigations in the 1870s. After studying habits of earthworms, he described the role that their movement of soil to the surface played in the burial of ancient monuments and in soil erosion.

— Charles Darwin.

|

Charles Darwin. The Structure and Distribution of Coral Reefs. London: Smith, Elder & co., 1874. Second edition, revised. [zoom] The colors on Darwin’s map correspond to three different types of coral reefs: atolls or lagoons, fringing reefs, and barrier reefs. Darwin believed that atolls and barrier reefs formed during periods of subsidence, when the land’s surface was gradually sinking. |

|

James Dwight Dana. Corals and Coral Islands. New York: Dodd & Mead, 1872. First edition. [zoom] | Additional images:

Darwin was compelled to publish an altered second edition of his Coral Reefs (1874), because of James Dwight Dana’s criticisms in this book. Dana (1813-1895) was a geologist at Yale University. |

|

Photograph of Charles Darwin’s sons with their Uncle Erasmus.

From left: Horace, Leonard, Erasmus, Francis, and William. Francis (holding the flute) played his bassoon to test the response of his father’s earthworms. William, to the right, who had been the subject of Darwin’s studies of infant expression, helped with much of his father’s botanical work. Original held by the English Heritage Photo Library. |

|

Charles Darwin. The Formation of Vegetable Mould, Through the Action of Worms, with Observations on their Habits. London: J. Murray, 1881. First edition. [zoom] This worm casting brought to the surface by an earthworm, came to Darwin from a correspondent in Bengal. It was almost three inches tall. |

|

Cross-section of Roman ruins buried by earthworms.

A cross-section of ruins of a Roman town, Silchester, Hampshire, drawn by the Reverend J. G. Joyce who oversaw the excavation. Darwin’s sons, Francis and Horace, visited the site and added their notes to Joyce’s in order to help their father determine the role of worms in burying archeological remains. Original held by the Cambridge University Library. |

|

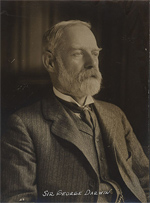

George Howard Darwin (1845-1912). [zoom] Darwin’s mathematical son carefully calculated the amount of soil that could erode from the hillsides to the bottom of a particular valley. If it had not been for earthworms, the soil would have remained under the earth’s surface. George later became the Plumian Professor of astronomy and experimental philosophy at the University of Cambridge. |

|

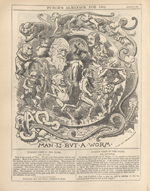

Man is but a Worm. Punch. London, 1882. [zoom] An example of the many cartoons published following the appearance of Darwin’s books on human descent, expression, and earthworms. |