Abraham Lincoln & Modern Politics

The rise of inexpensive photography in the 1850s and 1860s helped transform American electoral politics. Widespread distribution of photographic portraits gave supporters and voters a greater sense of connection to the candidates. A compelling photograph could create a visceral reaction in voters that no campaign platform could match.

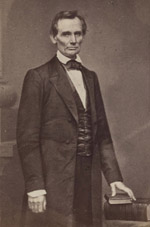

Abraham Lincoln (1809-1865), was the most photographed American of the 19th century. His central role in the nation’s most turbulent years and his rugged, world-weary features combined to make him a favorite subject for photographers of his time and for collectors ever since. Lincoln himself acknowledged the influence of Mathew Brady’s 1860 photograph of him saying, “Brady and the Cooper Institute made me President.”

Recognizing the camera’s power, Lincoln made extensive use of photographs during his presidency. He often sat for the leading photographers of the day, allowing them to distribute his image widely. He was generous in signing cartes de visite for admirers. To commemorate his long friendship with Joshua Speed, Lincoln inscribed the special large-format photograph seen in this exhibition.

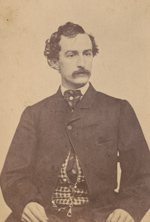

Lincoln’s assassination further cemented the vital place of photography in America. Countless men and women wore mourning pins with the martyred president’s photograph and displayed his portrait in their homes. John Wilkes Booth was tracked down in part because his photograph was well known, both from the theater and from wanted posters. When the conspirators were hanged, Alexander Gardner was there to capture the event in an early instance of photojournalism.

Mass production of photographs and their use in campaigns and memorials ensured that Lincoln’s face was and would remain better known than any president since George Washington.

|

Unidentified. Abraham Lincoln, Inscribed by Lincoln to Fanny Speed, March 1 to June 30, 1861. [zoom] Salted paper print, 11 ½ x 9 ½ in. This is likely the first image to capture Abraham Lincoln in his role as President. The rare, large format portrait is warmly inscribed to Fanny, the wife of Joshua Speed, Lincoln’s oldest and closest friend: “To my good friend, Mrs. Fanny Speed A. Lincoln.” The President almost certainly gave the portrait to Fanny when the Speeds dined at the White House on Thanksgiving Day, 28 November 1861. This extraordinary memento of Lincoln’s personal life documents one of his longest and most important friendships. On loan from the Stephan and Beth Loewentheil Family Photographic Collection. |

|

Mathew Brady. Abraham Lincoln, the Cooper Union Portrait, 1860. [zoom] Albumen print, carte de visite mount Brady’s famous Cooper Union portrait of Lincoln was taken the day of Lincoln’s celebrated speech at New York’s Cooper Union. The address played a central role in bringing Lincoln to national prominence and catapulted him into contention for the presidential nomination. The image was widely reproduced both as a photograph and in prints. Lincoln is said to have declared, “Brady and the Cooper Institute made me President.” |

|

Unidentified. Earliest Use of Photographs on a Campaign Badge, 1860. [zoom] Tintype , ¾ x ¾ in. The highly contentious 1860 presidential campaign pitted Lincoln against Douglas, Bell, and Breckinridge. With the Union threatened, the election’s stakes were high, and campaign paraphernalia was produced in unprecedented numbers. Presidential campaigns embraced photography as a way to tie supporters and candidates more closely and to capitalize on the power of image recognition, ushering in a new era in American electoral history. |

|

Brady’s Gallery. Presidential Campaign Badge, 1864. [zoom] Albumen print, 1 1/4 x 1 Gift of Gail ’56 and Stephen Rudin. |

|

Alexander Gardner. John Wilkes Booth, ca. 1860. [zoom] Albumen print, carte de visite mount John Wilkes Booth was one of the most famous American actors of the day. Consequently his photograph was widely available commercially as a carte de visite even before he assassinated Lincoln on April 14, 1865. |

|

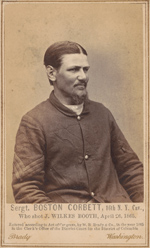

Mathew Brady. Boston Corbett, 1865. [zoom] Albumen print, carte de visite mount Corbett served in a Virginia cavalry unit in the hunt for John Wilkes Booth. On April 26, 1865, his regiment surrounded a barn in which Booth and David Herold were hiding. When setting the barn on fire failed to drive Booth out, Corbett shot him, violating Secretary of War Stanton’s orders. When asked why he did it, Corbett declared, “Providence directed me.” |

|

Alexander Gardner. Lincoln Assassination Conspirators Edmund Spangler and Lewis Payne (aka Powell), 1865. [zoom] Albumen print, 8 1/2 x 4 1/4 Additional images:

Lewis Powell, also known as Lewis Payne, was one of the assassination conspirators. Booth ordered Powell to go with David Herold to assassinate Secretary of State Seward in his home. Seward survived the knife attack, and Powell was tried and hanged. Spangler, who worked at Ford’s Theatre, was found guilty of conspiring with Booth and others and was sentenced to six years in prison. |

|

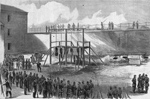

Alexander Gardner (original photograph). Execution of the Lincoln Conspirators. Wood engraving from photograph taken on July 7, 1865. New York. Harper’s Weekly. July 22, 1865. [zoom]

Lewis Powell (aka Payne), David Herold, George Atzerodt, and Mary Sarratt were convicted for conspiring with John Wilkes Booth in the assassination of Lincoln and the attempted assassination of Secretary of State Seward. The four were hanged at the Old Arsenal Penitentiary on July 7, 1865. Alexander Gardner (1821-1882) was the only photographer permitted to document the execution, and his photographs were quickly reproduced as wood engravings in Harper's Weekly. |

|

Anthony Berger, Brady's Gallery. Lincoln Mourning Pin, 1865. [zoom] Albumen print, 1 x 3/4 in. |

|

Letter on New York in Mourning. Written by a Union soldier staying at the Hotel Lafayette in New York, April 21, 1865. [zoom] Additional images:

After Lincoln’s death on April 15, 1865, much of America went into deep mourning. In this letter a soldier reports on the transformation of New York in the wake of the assassination: “Almost every house is in mourning, some of them having more than one hundred yards of crepe in festoons about the windows and doors. The whole city ... is so thickly draped in mourning as to make the front of nearly every building look black when you cast your eye up and down the street.” Gift of Gail ’56 and Stephen Rudin |

|

Lincoln Cent, 1909. [zoom] | Additional images:

To commemorate the 100th anniversary of Lincoln’s birth in 1809, Theodore Roosevelt authorized the creation of a one-cent coin with Lincoln’s portrait. No likeness of an historical figure had previously appeared on a circulating United States coin. When it was released, long lines formed to acquire the now-iconic coin. 500 billion Lincoln cents have been produced, making this the most-reproduced portrait in history. Gift of Gail ’56 and Stephen Rudin. |

|

Anthony Berger, Brady’s Gallery. Abraham Lincoln, February 9, 1864. [zoom] Albumen print, carte de visite mount This photograph served as the basis for sculptor Victor David Brenner’s bronze plaque of Lincoln. When Roosevelt saw the plaque, he suggested that Brenner be engaged to use the image for the design on the planned U.S. one-cent coin. Gift of Gail ’56 and Stephen Rudin. |