Celebrity Culture

(Albumen Prints, Cartes de Visite and Cabinet Cards)

The development of a mass audience for photography required the creation of a simple method for printing high-quality images on paper. Talbot and his successors had used salted paper coated in silver nitrate (salted paper prints), but the resulting mat surface produced undesirably soft images. The next great advance came in 1850 with Louis-Désiré Blanquart-Evrard invention of albumen paper.

Coating paper with egg whites (i.e. albumen) gave it a glossy, smooth veneer, which suspended light sensitive materials on the paper’s surface. No longer embedded in the fibers, the image floated on the paper’s surface, which improved the saturation of tones. Albumen paper, combined with the wet plate collodion, made it possible for photographers to mass-produce high-quality, inexpensive photographs. The stage was set for one of the most extraordinary periods of photographic history—the age of the carte de visite.

In 1854 a French photographer, André-Adolphe-Eugène Disdéri, introduced the carte de visite (a 2 1/8 x 3 ½ in. photograph mounted on a 2 ½ x 4 in. card) and a camera capable of exposing eight photographs on one 8 x 10 inch negative, enabling photographers to produce hundreds, instead of dozens, of images each day.

Owning portraits of famous men and women—or of oneself and one’s family—had been a privilege reserved primarily for the wealthy. By the 1860s, the carte de visite allowed virtually anyone to buy affordable likenesses of politicians, actors, authors, clergymen, generals, celebrities, and loved ones.

Actors distributed autographed cartes de visite to promote their careers. Abolitionists funded their campaigns by selling portraits of slaves showing the scars from their masters’ whips. Families and friends exchanged their own portraits in vast numbers. Cards of the most famous sitters sold over 100,000 copies. By 1862, the craze for these cards—called “cardomania” at the time—led poet and physician Oliver Wendell Holmes to note, “Card portraits as everybody knows have become the social currency, the green-backs of civilization.”

By the 1870s the carte de visite was superseded by the larger cabinet card, measuring 4 ¼ x 6 ½ in., which remained in vogue until the end of the century.

|

André-Adolphe-Eugène Disdéri. Uncut Sheet of Carte de Visite Photographs, 1860s [zoom] Albumen print, 7 3/4 x 9 in. In 1854 French photographer Disdéri (1819-1889) invented a camera capable of exposing eight carte de visite size images on a single negative using a four-lens camera with a sliding plate holder. This sheet of Disdéri photographs shows the print in the original state before cutting and mounting. Disdéri’s invention, together with the wet plate collodion negative and albumen paper, brought about a new era of low cost and mass-produced portrait photography. |

|

Disderi & Co. Portrait Of André-Adolphe-Eugène Disdéri, 1860s. [zoom] Albumen print, carte de visite mount |

|

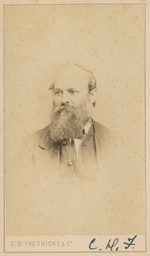

C. D. Fredricks & Co. Charles D. Fredricks, 1860s. [zoom] Albumen print, carte de visite mount Photography entrepreneur Charles D. Fredricks (1823-1894) was one of the first Americans to produce cartes de visite. He was a leading competitor of Brady and Gurney who, like Fredricks, had elaborate galleries on Broadway in New York. Fredricks specialized in cartes de visite and is said to have been the largest producer of the photographs in America. One contemporary wrote, “Some of the Parisian Galleries were fine, but nothing to be compared with Fredricks', and the finest establishments in London did not bear slightest comparison.” |

|

Samuel Clemens's Carte de Visite Album, annotated in his hand, 1860-1870s. [zoom]

With the growing phenomenon of collecting celebrity and family cartes de visite, manufacturers designed photograph albums specifically for the carte-size print. Clemens likely personally chose these photographs for a souvenir album compiled during a visit to Paris. The album documents the author’s awareness of and interest in French literature, culture, and celebrities. |

|

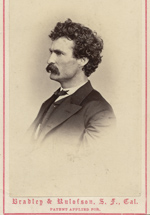

Bradley & Rulofson. Samuel Clemens, April 1868. Inscribed on the verso: “Yours Truly, Sam Clemens, Mark Twain.” [zoom] Albumen print, carte de visite mount Samuel Clemens (1835-1910), better known as Mark Twain, was photographed frequently throughout his career as a leading American author and humorist. In a letter to the Sacramento Daily Union in 1866, he wrote that photography “transforms into desperadoes the meekest of men … gives the wise man the stupid leer of a fool, and a fool an expression of more than earthly wisdom …The sun never looks through the photographic instrument that it does not print a lie ... I speak feeling of this matter, because by turns the instrument has represented me to be a lunatic, a Solomon, a missionary, a burglar and an abject idiot, and I am neither.” |

|

Photographicon, ca. 1865. [zoom]

Carte de visite mania led to a stream of inventions specially adapted for viewing and storage of the photographs. The parlor activity of examining cartes generated demand for viewing boxes, rotating display stands, elaborate frames and albums, scopes with flip-up magnifiers, and devices like Robinson’s Patented Photographicon, in which cartes are displayed on a tape controlled by turning spindles. |

|

B. F. Smith & Son. Frederick Douglass, 1860s. [zoom] Albumen print, carte de visite mount Frederick Douglass (1818-1895) was the leading African-American abolitionist. After escaping slavery, he joined the abolition movement, gaining fame as an author and orator. He stood as a living counter-example to slaveholders’ arguments that slaves did not have the intellectual capacity to function as independent American citizens. Douglass said, “What to the slave is the 4th of July?” |

|

Unidentified. Belva Ann Lockwood, 1860s. [zoom] Albumen print, carte de visite mount Belva Ann Lockwood (1830-1917), an early suffragist, became in 1879 the first woman to practice law before the United States Supreme Court. The first woman to appear on official presidential ballots, Lockwood ran for president in 1884 and 1888 on the ticket of the National Equal Rights Party. Her name and image were used here to advertise the tobacco products of W. Duke, Sons & Co. |

|

Wenderoth & Co. Bearded Lady, 1860s. [zoom] Albumen print, carte de visite mount |

|

W. & D. Downey. “The Two-Headed Nightingale,” 1860s. [zoom] Albumen print, carte de visite mount Conjoined twins Millie and Christine McCoy (1851-1912), born into slavery, were sold at birth to a showman named Smith. After recovering them from a kidnapper, Smith and his wife provided the twins with an education and taught them to speak five languages, dance, play music, and sing. The twins enjoyed a long, successful career and appeared frequently with the Barnum circus. Though each had two legs, one leg was held in out of sight in this pose to make the pair look more curious, thereby stimulating interest in the performers. |

|

Alfred Brisbois. William “Buffalo Bill” Cody, late 1880s. [zoom] Albumen print, cabinet card mount The widespread availability of photographic images of heroes such as William F. Cody, the celebrated American scout and showman, was central to the creation of the mythology of the American West. Photographs of famous individuals from many fields of endeavor helped to produce a vibrant celebrity culture in the United States. |

|

Conly's Portraits. Louisa May Alcott, 1870s. [zoom] Albumen print, cabinet card mount Louisa May Alcott (1832-1888) is the beloved children’s author most famous for Little Women. The oft-reprinted novel, which has been made into numerous film versions, was loosely based on Alcott’s childhood with her father, Transcendentalist Bronson Alcott, her mother, and three sisters. |