The World In Three Dimensions

Nineteenth-century Americans were captivated by the three-dimensional images produced with the stereograph, made up of a double image on a single card. When viewed through a binocular device called a stereoscope, the two images merge to produce a sense of “relief or perspective,” the 19th century’s version of 3-D. Struck by the sense of reality experienced though stereovision, Oliver Wendell Holmes said, “It is a leaf torn from the book of God’s recording angel.”

Stereovision was first described in 1838 by English scientist Charles Wheatstone, author of Phenomena of Binocular Vision and inventor of the stereoscope. Introduced just before the advent of photography, the first stereographs were drawn by hand. Later stereographs appeared in each of the successive popular forms of photography, including daguerreotypes, tintypes, and paper prints. As photography improved, stereographs became increasingly popular for entertainment, education, and virtual travel. A German visitor to the United States in the 1880s, Dr. Hermann Vogel, remarked at a photographer’s conference, “I think there is no parlor in America where there is not a Stereoscope.” The stereograph remained popular into the 1920s.

|

J.E. McClees and W.L. Germon. Father and Son in a Mascher Stereoscope Case, ca. 1853. [zoom] Hand-colored daguerreotypes, sixth plates John F. Mascher patented this ingenious case in 1853. The dual image, captured stereoscopically, can be viewed in three dimensions with a pair of lenses that fold out from the viewing case. |

|

"The Saturn Scope." [zoom]

A staggering variety of stereoviewers were made during the long stereograph period (1839-1930s). This handheld “Saturn Scope,” patented by James M. Davis in 1883, represents the most common version. Oliver Wendell Holmes designed a similar viewer in 1859. |

|

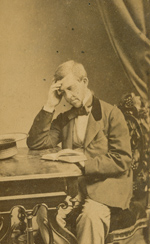

Black & Batchelder. Oliver Wendell Holmes, ca. 1860. [zoom] Albumen print, carte de visite mount Oliver Wendell Holmes (1809-1894), a leading physician and popular author, was a promoter of the art of photography. He called stereographs “sun sculptures” and invented a handheld stereoscope similar to the one in this case. About stereographs Holmes wrote, “All pictures in which perspective and light and shade are properly managed, have more or less the effect of solidity; but by this instrument that effect is so heightened as to produce an appearance of reality which cheats the senses with its seeming truth.” |

|

Lewis M. Rutherford (attributed to), published by John P. Soule. "Full Moon,” 1864. [zoom] Albumen prints, stereograph mount This famous photograph of the moon, published as a stereograph by John P. Soule, was taken in 1864 by Lewis M. Rutherford (1816-1892), the “Father of Celestial Photography.” Rutherford invented the first telescope made specifically for astrophotography. |

|

Photographer unidentified, published by Kilburn Brothers. “Distinguished Southerners Grinding Cane,” ca. 1879. [zoom] Albumen prints, stereograph mount Frederick Douglass said in 1849, “Negroes can never have impartial portraits at the hands of white artists. It seems to us next to impossible for white men to take likeness of black men, without most grossly exaggerating their distinctive features.” The racist comic photograph, an enormously popular genre, was but one element of the nationwide campaign to subjugate African-Americans in the post-Reconstruction period. |

|

Unidentified, “The Old Chief, The Beaver's Camp,” 1879. [zoom] Hand-colored albumen prints, stereograph mount |

|

Photographed and published by Eagles. “Cornell University Buildings from Sage College, Ithaca, N.Y.,” ca. 1882. [zoom] Albumen prints, stereograph mount Additional images:

|