Faithful Companions:

Rocinante

Rocinante is the name of Don Quixote de la Mancha’s skinny and clumsy horse, in the universally acclaimed novel Don Quixote by Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra, published in 1605, with a second part in 1615. Though he is supposedly the great-grandson of El Cid’s famous horse Babieca, Rocinante does not possess the flamboyant qualities you would expect from the steed of a legendary knight, the kind admired by his master, a decrepit country gentleman driven insane by reading too many chivalric romances. Indeed, Rocín in Spanish means “work-horse” or “nag” - even though Rocinante is heralded as “superior to Bucephalus” in the fantasy world created by his master. Don Quixote and Rocinante have remained a source of empathetic inspiration for many artists since the very first illustrations in Shelton’s 1612 English translation.

|

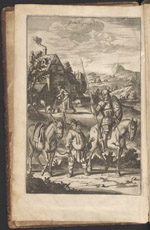

[Cervantes]. The History of the Most Renowned Don Quixote of Mancha and his Trusty Squire Sancho Pancha now Made English According to the Humour of our Modern Language and Adorned with Several Copper Plates. London: Thomas Hodgkin, 1687. [zoom] | Additional images:

John Phillips, Milton’s nephew, produced this illustrated English edition of Don Quixote, with fourteen anonymous copper engravings plus a frontispiece image introducing the main protagonists to the reader. |

|

[Cervantes]. Don Quichotte de la Manche, traduit de l’espagnol par Florian. Paris: Didot l’aîné, 1799. [zoom] This delicate vignette shows Don Quixote once again about to fall from his horse, a metaphor for his constant setbacks and brutal confrontations with reality. |

|

[Cervantes]. Don Quijote de la Mancha, ilustrado por Salvador Dalí, Barcelona: Mateu, 1965. [zoom] | Additional images:

Many illustrated editions of Don Quixote were produced in the 20th century. According to the curators of a 2005 exhibition at the George Peabody Library, “it was Salvador Dalí who represented a radical break with the past. His 1946 illustrations [for Random House in New York] portrayed both the conscious and unconscious worlds of Don Quixote: one world could not be separated from the other in Dali’s surrealistic vision.” Indeed, Dalí said he wanted to “systematize confusion thus help discredit completely the world of reality,” a goal that would have appealed to Don Quixote’s himself. |

|

[Cervantes]. Don Quijote de la Mancha, with A Lectura del Quijote by Antonio Saura, Barcelona: Círculo de Lectores, 1987. [zoom] On loan, courtesy of Dr. María Antonia Garcés. When he was very young, Spanish artist Antonio Saura (1930-1998) made a list of books he would like to illustrate (San Juan de la Cruz, Cervantes, Kafka, Orwell… ) He described the process of illustrating Don Quixote as grueling and exhausting, “a graphic sword fight.” His seventy-one minimalist drawings, with their strokes in black ink, are imbued with a subtle irony, and avoid the clichés of “folkloric Spain.” |

|

[Cervantes]. L’Ingénieux hidalgo Don Quichotte de la Manche, illustré par Gérard Garouste.Paris: Diane de Selliers, 1998. [zoom] This image illustrates the episode in which Don Quixote attacks a funeral procession, for he believes that “an image which the mourners carried, all covered with black, was some lady whom those scoundrels had kidnapped.” Dressed in white, the pure yet foolish hero is one with his comic-strip horse. Indeed, Gérard Garouste (b. 1946) argues that “Sancho, his donkey, Don Quixote and Rocinante form but one person with different facets.” |