There and Back Again: Dark Journeys and Heroic Quests

Not all those who wander are lost…

– J.R.R. Tolkien, The Fellowship of the Ring.

Mythologist Joseph Campbell identified a recurring story structure, the “Hero’s Journey,” that appears in myths and folklore throughout the world:

- A hero ventures forth from the world of common day into a region of supernatural wonder: fabulous forces are there encountered and a decisive victory is won: the hero comes back from this mysterious adventure with the power to bestow boons on his fellow man.

–The Hero With a Thousand Faces (1949).

It is a pattern that children’s and teen literature have also frequently adopted, particularly – well, obviously – in the fantasy genre. The appeal is similar to that of fairy tales: young readers want to identify with the hero, who is especially chosen from the masses of ordinary children for a dangerous quest that no one else can complete. And besides, who doesn’t want to believe in magic? At an age when the dreary truths behind mysteries like Santa and the Tooth Fairy have all been revealed, these stories allow children to inhabit a world where magic is real, and is only a wardrobe-door away for those who know where to look.

|

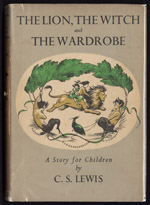

C.S. Lewis. The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe; A Story for Children. Illustrated by Pauline Baynes. London: G. Bles, [1950]. First edition. [zoom] Additional images:

Lewis was both a scholar of medieval literature specializing in allegory and a Christian apologist, so it’s no surprise that these elements all found their way into the Chronicles of Narnia, his fantasy series for children. The first book, a story of four children who are transported to a land of talking animals to rid them of an evil witch and rule as kings and queens, is rife with Christian symbolism – which some consider incongruous in a novel populated by witches and sentient animals. Young readers don’t seem to mind. |

|

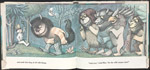

Maurice Sendak. Where the Wild Things Are. New York: Harper & Row, ca. 1963. [zoom] Additional images:

This Caldecott Award-winning story of a willful boy who travels across the ocean and becomes king of the hard-partying Wild Things, basically to spite his mom, was a milestone in picture book publishing. Nearly 50 years later, Sendak’s stunning illustrations still perfectly capture the delightfully dangerous world of Max’s imagination. |

|

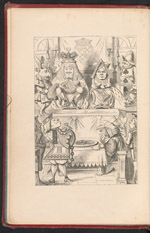

Lewis Carroll. Alice's Adventures in Wonderland. Illustrated by John Tenniel. London: Macmillan and Co., 1866. First edition. [zoom] Additional images:

It would be hard to overstate the impact that Carroll’s twin fantasy novels have had on the field of children’s literature, and on the public consciousness in general. Wonderland and its inhabitants have become archetypal symbols for madness and chaos. Alice succeeds in navigating this hallucinatory terrain with a winning combination of childish innocence, logic in the face of nonsense, and defiance of a world that refuses to play by its own rules. |

|

Lewis Carroll. Alice’s Adventures Under Ground. [1951]. A facsimile of the original manuscript book (later developed into Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland) now held by the British Library. [zoom] Carroll (a.k.a. Charles Dodgson) was an amateur photographer – a relatively new thing to be in the 1860s – and among his favorite models was a girl named Alice Liddell. He spontaneously invented a nonsense story for Alice and her sisters on a boat trip, and at her request wrote it down for her. He then expanded the story and hired John Tenniel to illustrate it for publication. The thought of a bachelor professor spending so much of his time with little girls, and the… ahem, artistic ways he photographed them, raises a lot of eyebrows now. In the Victorian era, though, nude children were sometimes featured in art as a personification of Eden-like innocence. |

|

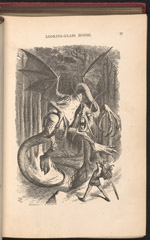

Lewis Carroll. Through the Looking-glass, and What Alice Found There. Illustrated by John Tenniel. London: Macmillan and Co., 1872. First edition. [zoom] Additional images:  Additional images: Additional images:

Alice’s second journey, this time through a mirror into a backwards looking-glass world, has proven just as popular as the first. Both were revolutionary for being purely fantastical and fun in an era when children’s literature was almost always didactic. Carroll’s clever wordplay and ability to portray dream-logic in writing have kept readers entertained ever since. |

|

L. Frank Baum. The Wonderful Wizard of Oz. Chicago; New York: G.M. Hill Co., 1900. [zoom] Additional images:  Baum’s heroine Dorothy Gale is the most obvious heir to Alice’s legacy. But the world she must traverse is much deadlier: she and her companions survive attacks by wolves, bees, crows, soldiers and winged monkeys before they can complete their quest to kill the witch.

Baum’s heroine Dorothy Gale is the most obvious heir to Alice’s legacy. But the world she must traverse is much deadlier: she and her companions survive attacks by wolves, bees, crows, soldiers and winged monkeys before they can complete their quest to kill the witch.

|

|

J.R.R. Tolkien. Autographed letter. October 25, 1958. [zoom] Additional images:

|

|

J.R.R. Tolkien. The Hobbit; or, There and Back Again. Illustrated by Alan Lee. New York: Houghton Mifflin, 1997. 60th anniversary edition. [zoom] Tolkien was a good friend and fellow Oxford professor of C.S. Lewis. His area of expertise was in Anglo-Saxon literature and Norse mythology, which inspired some of the creatures that inhabit his fantasies: dwarves, elves, trolls and dragons. Bilbo, the home-and-hearth loving hobbit, must encounter all of these and more as he makes his way across Middle-Earth, becoming the perfect Campbellian hero along the way. |