Secret Lives: Real Toys and Talking Animals

Real Toys

As the wise old Skin Horse tells the Velveteen Rabbit: “When a child loves you for a long, long time, not just to play with, but REALLY loves you, then you become Real."

To an adult, that teddy bear is just a stitched-together bundle of fake fur and fluff; but if you’re a child, it’s the perfect companion: always available, never complains, and keeps all your secrets. So of course it’s going to get into mischief when everyone’s back is turned – that’s exactly what you do, too. The fact that grown-ups don’t believe it’s real? Well, that’s just further proof of how little they know about your world.

|

A.A. Milne. Winnie-the-Pooh. Illustrated by Ernest H. Shepard. London: Methuen & Co., Ltd., 1926. [zoom] A.A. Milne famously based the characters of his beloved books on his own son, Christopher Robin Milne, and his toys. As an adolescent Christopher came to resent the exploitation of his childhood and the unwelcome attention and teasing he endured at school. He gave away the original toys, which are now on display at the New York Public Library. |

|

A.A. Milne. Autographed letter. No date. [zoom] Additional images:

Milne’s plea on behalf of a charity that sends underprivileged city children for a two-week holiday in the country modestly makes no mention of his position as a famous author. It is also ironic that he seems so concerned with the welfare of strangers’ children, while his own son was largely raised by a nanny. |

|

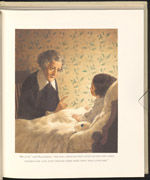

Margery Williams [Bianco]. The Velveteen Rabbit, or, How Toys Become Real. Illustrated by William Nicholson. Classic edition. New York: Doubleday, 1991 (first published 1922). [zoom] If a child’s love can make a toy Real, then what happens when that toy is outgrown or discarded? Williams lets fickle children off the hook with the Nursery Magic Fairy’s promise to make [words missing here?]. A Velveteen Rabbit is rescued from the trash pile and becomes a living, leaping, frolicking rabbit. |

|

Rachel Field. Hitty, Her First Hundred Years. Illustrated by Dorothy P. Lathrop. New York: Macmillan, 1929. [zoom] A plucky, self-possessed wooden doll is exposed to the best and the worst of human nature, and a century of world history, as she is repeatedly lost, found, and passed between owners. |

|

Lynne Reid Banks. The Indian in the Cupboard. Illustrated by Brock Cole. Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, ca. 1980. [zoom] A boy gets to play god, and receives an intense lesson in responsibility, when he acquires a magic key-and-cupboard combo that brings his Native American figurine to life. |

|

Kate DiCamillo. The Miraculous Journey of Edward Tulane. Illustrated by Bagram Ibatoulline. Cambridge, Mass.: Candlewick Press, 2006. [zoom] Additional images:

Like the love child of Pinocchio and Hitty, a vain, spoiled toy rabbit is lost at sea and undergoes a series of hardships as he’s passed between owners – turned into a marionette, crucified as a scarecrow, and smashed to pieces – before he learns to love them back. Finally he is reunited with his first owner, now a grown woman with a daughter of her own. |

Talking Animals

“Children tell little more than animals, for what comes to them they accept as eternally established.” – Rudyard Kipling

Toys aren’t the only ones leading secret lives. Children’s books are full of animals who talk, wear clothes, and generally carry on like furry and feathered people – all right under the noses of unsuspecting grown-ups. Young readers have no problem with the ideas of anthropomorphized animals or oblivious adults.

|

Rudyard Kipling. The Jungle Book. Illustrated by J.L. Kipling, W.H. Drake, P. Frenzeny. London: Macmillan and Co., 1894. [zoom] Additional images:

In the most famous of Kipling’s stories, a baby boy is found in the Indian jungle, and raised by the animals that find him. Mowgli learns their languages and ways – and so is called a sorcerer by uncomprehending adults when he tries to return to the society of humans. |

|

Photograph album of Rudyard Kipling and family in India, ca. 1886. [zoom] Rudyard Kipling (1865-1936) spent the first few years of his life as an Anglo-Indian – an English person living in British-controlled India – and returned again as a teenager. The experience of growing up between two cultures had a profound impact on his development, and became a recurring theme in his stories. |

|

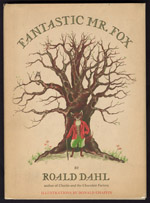

Roald Dahl. Fantastic Mr. Fox. Illustrated by Donald Chaffin. New York: Knopf, 1970. [zoom] Additional images:

Roald Dahl’s dapper hero proves just how fantastic he is by repeatedly outwitting the three human farmers bent on his demise, stealing their food to feed his family and the entire animal neighborhood. |