Lincoln’s Image

Through photographs, paintings, prints, and sculptures, Lincoln left behind a surprisingly rich archive of his likeness. He sat patiently for an estimated 120 photographs during his years as a politician (1847 - 1865) and made himself accessible to a number of painters and artists.

Lincoln’s political rise coincided with an explosive increase in the availability of commercial photography. He entered the White House the same year that mass-produced cartes de visite (small photographs printed on card stock, and used initially as calling cards) generated a craze for collecting the pictures of friends, family, and famous people. The mid-nineteenth century also saw the rise of the illustrated newspaper, and the proliferation of all kinds of prints and engravings, making it possible for ordinary people to see and own images on an unprecedented scale. These technological and social trends, combined with Lincoln’s achievements and his early death, explain the extraordinary number of contemporary illustrations and portraits of Lincoln that survive today.

|

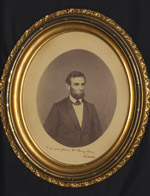

Abraham Lincoln. Signed Salt Print Portrait. Photographed between March 1, 1861 and June 30, 1861. [zoom] This photograph of Lincoln was taken either just before or shortly after his first inauguration. Lincoln inscribed it to Mrs. Fanny Speed, the wife of his oldest friend, Joshua Speed. Scholars cannot yet identify the photographer, but they believe that Lincoln probably inscribed and presented the portrait to Mrs. Speed on Thanksgiving Day, November 28, 1861, when the Speeds dined with the Lincolns at the White House. Lincoln met Joshua Speed in 1837, when he arrived in Springfield, Illinois. Speed remained Lincoln’s closest friend for the rest of his life. From the collection of Stephan Loewentheil. |

|

Leonard Wells Volk. Abraham Lincoln Modeled from Life, 1860. Copy in Bronze. [zoom] | Additional images:

On March 31, 1860, Lincoln went to the Chicago studio of sculptor Leonard Volk to have a wet-plaster life mask made. Then just beginning his campaign for the Presidency, he must have seen the political potential and publicity value of having his likeness thus immortalized. Lincoln commented, however, that “the process was anything but agreeable.” Volk would use the cast as the source for multiple plaster and bronze busts, in both “nude” and classically draped versions. Several public statues and monuments further adapted Volk’s work, making it one of the more familiar renderings of Lincoln’s image. This later 19th century casting has been attributed as being a gift of Cornell University’s first president, Andrew Dickson White, but is believed to have been given to Cornell for the library's the Historical Seminary room by J. E. Rankin of Ithaca in 1892. |

View an image of this exhibition case: 1