Lafayette & Women

In terms of his relationships with women, Lafayette was not quintessentially different from other aristocrats of his time: he dutifully accepted an early marriage of convenience, and later pursued extra-marital flirtations (well into an advanced age, according to Stendhal) and friendships with “muses.” On the other hand, he also shared attitudes more typical of the bourgeoisie of the romantic era. with his correspondence contains many expressions of genuine conjugal love, and reflects a lively interest in children, his own as well as those of his friends and family members. Finally he supported women’s rights, particularly in matters like education and divorce.

|

Financial Contract of Lafayette’s Marriage to Adrienne de Noailles, 1772. [zoom] A marriage under the Old Regime was mostly about alliances and money. The deal between the Duke d’Ayen and Gilbert’s grandfather, the ultra-wealthy Comte de La Rivière, was kept secret until the girl was thirteen and the boy sixteen. The terms were extremely precise. Article 12 stipulated that, should Gilbert die first, she would keep “her clothes, linens, diamonds and jewelry, and a carriage with six horses”; should she die first, he would keep his “clothes, linens, arms, a carriage with six horses, and his library”. It was also agreed that the young couple would live with the Noailles-Ayen family for the first two years after the marriage. The union turned out to be a happy one, until Adrienne’s death in 1808. |

|

Marie Hortense de La Tour d’Auvergne, Duchesse de La Trémoille. Letter to Lafayette’s Aunt. November 29, 1772. [zoom]

I told [the Comte de la Rivière] that his grandson had no interest in buying Mlle de Noailles if he has to renounce his rights to get her. He said that it was absolutely not the case: Gilbert will be given 200,000 livres... I also know that Mme. d’Ayen shall not show any favoritism towards her other children. You may ignore that this lady has only five daughters and no son. The older one will be married to the second son of the Comte de Noailles; the second one is for your nephew: a good marriage, and yet I would have postponed it by two more years. But the Comte de la Rivière is eager to give another father to his grandson... The most important thing is to provide the young man with a wise mentor, a religious man who might form his pupil by means of exercises and travels... Your nephew found his fiancée charming. She is said to be so, and well brought-up...

Lafayette’s marriage soon became the talk of the town. This letter reveals that the gossipy sixty-eight-year-old Duchess, a distant relative, was in the loop. By boarding his ship to America, Lafayette was also escaping this large and encumbering family. |

|

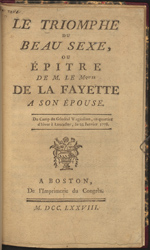

Le Triomphe du Beau Sexe, ou Épitre de M. le Marquis de La Fayette à son épouse: Du camp du Général Waginston [sic]. À Boston: De l’imprimerie du Congrès, [1778]. [zoom] | Additional images:

This schmaltzy anonymous poem celebrates the young Lafayette couple separated by the American War. Lafayette was aware that becoming a hero was as much a matter of publicity as of achievement. He employed propagandists and artfully used his young wife’s maternal graces in his personal publicity campaigns. |

|

Lafayette, His Wife, and Their Two Daughters Anastasie and Virginie in Olmütz. Engraving after Ary Scheffer, not dated [ca. 1830]. [zoom] During the Terror (1793-4), Adrienne’s grand-mother, her mother and one of her sisters were guillotined; she owed her life to the American ambassador Gouverneur Morris. Once free, she decided to join her husband in his prison at Olmütz (now in the Czech Republic). With her two daughters, she went to Hamburg, where the American consul issued passports to a “Mrs. Motier of Hartford, Connecticut”, granting them the right to travel to Vienna, where a “permit of incarceration” was delivered. She never recovered from her years of captivity and died in 1808. |

|

LaFayette. Letter to Vicomte de Noailles. October 3, 1780. [zoom]

... Damas had for me only compliments from the charming one [his wife Diane]: I received but one letter from her. Try to convince Lauzun or Dillon to sell me a flat tiger skin, and send it to me. My friend, politics bore me when there is no military dimension to it. I miss Paris and the local ladies a lot. I long to see you, your friendship would put me in good spirits...

Contrary to legend propagated by some well-intentioned hagiographers, many of whom liked to emphasize Lafayette’s “American” qualities, the young Frenchman was never unduly influenced by American “Puritanism.” While cautious, he admired well-known libertines of the day like the ultra-fashionable Armand de Lauzun (1747-1793), who had dissipated his fortune traveling about Europe, or Arthur Dillon (1750-1794), one of the thirty-six Irish officers who served in America. All used expensive tiger skins from India as saddle covers on horseback, and as capes when sitting for portraits. |

|

Elisabeth Vigée-Lebrun. Portrait of “Diane de Damas d’Antigny, Comtesse de Simiane.” Oil on Canvas (reproduction). [zoom] Diane de Simiane (1761-1835) was married to a homosexual courtier who served in America with Rochambeau and Lafayette; she became the latter’s mistress in the early 1780s. Celebrity portraitist Vigée-Lebrun noted in her diary: “M. de La Fayette came to my house for the sole purpose of seeing a portrait I was painting of the pretty Mme de Simiane, whom they say he was taking care of at the time...” His wife always proved very tolerant: she allowed her husband to spend vacation time with Diane, and encouraged her children to call her their “aunt”. |

|

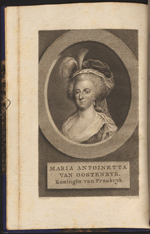

La Confession de Marie-Antoinette, Ci-devant Reine de France, au Peuple Franc, Sur Ses Amours et ses Intrigues avec M. de Lafayette, les Principaux Membres de l’Assemblé Nationale, et sur ses Projets de Contre-révolution. [Netherlands, i.e. Paris], 1792. [zoom] | Additional images:

This is one of many revolutionary pornographic pamphlets directed against Queen Marie-Antoinette, who was hated for her foreign origins (the portrait included in this pamphlet is entitled “Marie-Antoinette of Austria”) and for her costly extravagances. Because her marriage to shy Louis XVI had remained unconsummated for seven years, the couple made an inviting target. After Lafayette rescued them in October 1789, he became her alleged erotic partner (in this pseudo-confession, she says “I do everything with him [and] wouldn’t be surprised if a child results from our erotic parties”), along with other politicians, sex-crazed lesbians, her own son and even her spaniel... This type of underground literature, intended to dehumanize the Queen, helped to ruin the reputation of the monarchs and paved the way for their public execution. |

|

Revolutionary Fan Showing Marie-Antoinette and her Son (Lafayette is on the verso, along with King Louis XVI). [zoom] | Additional images:

Louis XVI was guillotined on January 21, 1793; Marie-Antoinette, on October 16 of the same year; and their son died in jail aged 10 on June 8, 1795. |