Lafayette The Abolitionist

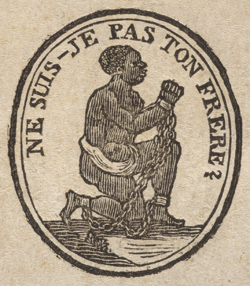

Lafayette always expressed paternalistic sympathies for “the black part of mankind.” His first encounter with slaves was with oystermen in South Carolina in 1777. He suggested using black troops in the American conflict and employed a former slave, James Armistead “Lafayette,” as a spy and trusted valet. By 1783, after reading Condorcet’s Réflexions sur l’Esclavage des Nègres (1781), he asked Washington to consider a joint venture for gradual emancipation; but he would conduct the experiment alone in the French colony of Cayenne. From then on, he became part of an international network of activists. His last known letter was addressed to an abolitionist society in Glasgow (May 1834). Such convictions passed to his family, and his grandson Gustave de Beaumont published a novel about racism and a (tragic) interracial union in the United States: Marie, ou l’Esclavage aux Etats-Unis (1836).

|

Jacques Nicolas Bellin. Map of the Guyanas, Including the French Guyana, on the Coast of South America, 1757. Private collection. [zoom] |

|

Intendant L. de Geneste. “List of Negro Slaves Selected by Daniel Lescallier” for Lafayette’s Experimental Plantation. March 1, 1789. [zoom] In 1785 Lafayette acquired a clove and cinnamon plantation called “La Belle Gabrielle,” along the Oyapok River in present day French Guiana. Here, he accomplished the “gradual emancipation” of nearly seventy slaves aged between 1 and 59, whom the administrator of Guyana helped to select. They were paid for their labor, were provided with education, and punishment for them was no more severe than for white employees. Lafayette hoped to show that productivity and the birth rate would rise and infant mortality would decrease under these “humanitarian” conditions, thus demonstrating the inutility of slave trade for economic exploitation. |

|

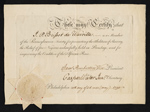

Pennsylvania Society for Promoting the Abolition of Slavery. Membership Certificate of Jacques Pierre Brissot de Warville, 1790. [zoom] French lawyer, journalist and political activist Jacques Pierre Brissot met with Lafayette in the mid-1780s in Franz Mesmer’s pseudo-scientific sect, whose members sought to “recreate the natural man” and “destroy the obstacles to universal harmony”. When he launched the Society of the Friends of Blacks in 1788, Gilbert and Adrienne de Lafayette joined the activist group, which had 141 members in 1789, including Lavoisier and several prominent financiers. As its president, Brissot toured the United States in 1788 and 1791 to promote the anti-slavery cause, and spent three days at Mount Vernon with Washington. Afterwards, he became a vocal supporter of the French revolutionary war, and denounced his former friend Lafayette as a traitor. Increasingly challenged by the left, he was guillotined in 1793. |

|

Slave Manacles. Virginia, 1865. [zoom] |

|

President James Madison. Letter to Lafayette. November 1826. [zoom] | View/download a PDF of this item

… You possess, notwithstanding your distance, better information concerning Miss Wright and her experiment, than we do here. We learn only that she has chosen for it a remote spot in... Tennessee, and has commenced her enterprise; but with what prospect, we know not... What would be simpler, with the requested grant of power to Congress, than to purchase all female infants at their birth, leaving them in the service of the holder to a reasonable age, on condition of them receiving an elementary education? The annual number of female births may be stated at twenty thousand; and the cost at less than one hundred dollars, at the most: a sum which would not be felt by the Nation, and even within the compass of State resources. But no such effort would be listened to... and it seems to be indelible that the two races cannot co-exist, both being free and equal. The great sine qua non therefore is some external asylum for the coloured race. In the meantime the taunts to which the misfortune exposes us in Europe are the more to be deplored, as they impair the influence of our political example…

This letter mentions slavery twice: Jefferson’s Monticello is to be sold “negroes included”; and Frances Wright, the thirty-one year-old daughter of a Scottish linen manufacturer, acquired 4,000 acres near Memphis and gave them to slaves bought from local farmers. This was inspired to a certain extent by what Lafayette (a man she admired so much that she called him “father” and sought adoption by him) had experienced in Guyana. Yet Wright’s promotion of “free love” was highly controversial, and the co-op did not last (1825-1828). The former slaves were re-settled in Haiti. |

|

“Sale of Estates, Pictures and Slaves in the Rotunda, New Orleans.” From James Silk Buckingham, Slave Estates in America. London, 1842. [zoom] | Additional images:

Lafayette could not have known the Rotunda, an infamous slave auction block described by the English journalist Buckingham (with whom he began corresponding in 1830), for it was built in 1838. Yet he witnessed similar scenes: “One was selling pictures; another was disposing of some slaves, an unhappy family exposed to the hammer at the same time. Their good qualities were enumerated in English and in French, and their persons were carefully examined by prospective purchasers.” |

|

Lafayette. Letter to his Daughters and Grand-daughters. New Orleans, April 15, 1825. [zoom] | View/download a PDF of this item

...This almost entirely French republic has something piquant... there is only one point to which I decidedly cannot resign myself: that is slavery, and the anti-Black prejudices. I believe that in this respect my travel might have been useful. The fact that I asked to meet with colored men who fought on January 8 was another proof of what I am preaching continuously, not for the beauty of it, but in order to bring gradual healing. In the current situation, it resides in the prospect of colonization in Africa as well as the easy move to Haiti, where there is plenty of space...

In this letter, Lafayette refers to the contribution of American Indians and African-Americans against Britain, which was forced to recognize claims on Louisiana and West Florida in January 1825. This achievement helped the abolitionist cause that Lafayette supported as Vice-President of the Society for the Colonization of Free People of Color of America, founded in 1816 “to help Blacks return to the land of their fathers.” Co-founders like Rev. Finley and Chief Justice Bushrod Washington saw the transportation of former slaves to Liberia as a charitable work that would both promote a gradual end to slavery and spread Christianity in Africa. Lafayette thought that Haiti, which had been “the first Negro state” since 1804, was another potential destination. |