“Any Person”

The university founded by Ezra Cornell and Andrew D. White pledged in its charter that it would be open to academically qualified “persons.” Other colleges educated the sons of those financially able to afford college, or those intending to become members of the clergy. Few schools were open to any person.

Did “any person” mean that those who were foreign-born would be welcome at Cornell? The answer was yes. Ezra Cornell boasted about the range of places from which the first students came, and he thought that Cornell really deserved university status when the first foreign student graduated in 1869. Arthur Bird of Haiti believed Ezra Cornell was speaking of him, but there were other foreigners at the university that first year: they came from Russia, England, Bulgaria, Hungary, and a number from Canada. In the university’s first twenty years, more than 120 foreigners took degrees at Cornell, while others came to study for a time, even if they did not stay for a full four-year course. Among them were more than thirty-four students from Brazil and eleven from Japan.

Any person also included African Americans. Laws throughout the South had barred them from receiving higher education. In the North, African Americans were generally admitted to public schools. By the outbreak of the Civil War, however, only a handful had earned a college degree, and many colleges refused to allow entrance to students of color.

Hearing of Cornell University in 1868, a man from Bermuda asked if Cornell would receive a black student who desired a professional education. A man from Ohio wrote to Ezra Cornell to ask if a black youth he knew could come to the university to study. Ezra Cornell answered, “Send him.” Although only a few African-American students attended Cornell during the university’s earliest years, there was no bar to their admission.

|

Malvina Higgins. Letter to Ezra Cornell. Maryville, East Tennessee, October 19, 1869. [zoom] | View/download a PDF of this item Malvina Higgins grew up in Ithaca. In the 1850s her family left the Presbyterian Church to form an Abolition Church in Ithaca. When grown, Malvina Higgins went to the south to teach in African-American schools. She wrote to Mr. Cornell in 1868, praising the new university in Ithaca that “ . . . such an institution as yours has taken this step in recognition of the brotherhood of man . . . it is so like the broad shining of the sun whose rays fall upon all with equal cheerfulness.” Mr. Cornell will permit one who has been teacher among the Freedmen in different states, to thus tax his valuable time with a note of thanks that he does not exclude colored persons from the benefits of his University. Seeing the universal horror with which such a suggestion is received in our schools at the south, and yet seeing that “Cornell” has become a subject of interest among the intelligent of these places far beyond my expectations, even, we can but regard this step in your institution as greater than a political victory—and an important aid in re-construction, notwithstanding the fact that a few northern colleges have thus done. That such an institution as yours has taken this step in recognition of the brotherhood of man seems to be of special consequence just now. . . . It is with pleasure, that on returning to East Tennessee, where this Maryville College has struggled so hard, I am able to say that the beautiful University which graces my home has taken this step.

|

|

John Corbin. Letter to Ezra Cornell. September 17, 1868. [zoom] | View/download a PDF of this item John Corbin wrote Mr. Cornell to ask if the university would accept a black student. Mr. Cornell’s handwritten answer was resolute and brief: “Send him.” |

|

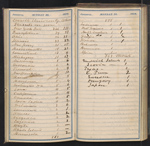

Ezra Cornell. Pocket Diary, 1870. [zoom] The diary includes notes, accounts, drafts and copies of letters, as well as a list of “where students are from.” In 1870, students came to Cornell University from twenty-eight states, Washington, D.C., and eleven foreign countries. In the first twenty years, the largest number of foreign students came from Canada. They were predominantly male; the first female foreign student, Canadian Margaret Henderson, graduated from Cornell in 1881. |

|

Thomas Budd. Letter to Ezra Cornell. London, England, September 28, 1868. [zoom] | View/download a PDF of this item Might a foreign-born boy come to the new university in Ithaca? Budd wrote to Ezra Cornell from England, where to be a scholar one needed to be a member of the Anglican Church. |

|

Paul C. Sinding. Letter to Ezra Cornell. Elmira, New York, February 17, 1868. [zoom] | View/download a PDF of this item In one of the leading papers in Copenhagen, Denmark, the great and almost unparalleled magnanimity and liberality you have shown in the establishing of the Cornell University . . . . has been the subject of an article . . . in which you very correctly are called: “the benefactor of mankind.”

|

|

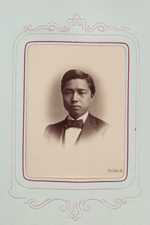

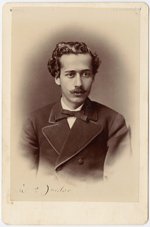

Ryokichi Yatabe, Class of 1876. [zoom] Cornell’s first Japanese graduate, Mr. Yatabe went on to become the first Professor of Botany and Curator of Botanic Gardens at the University of Tokyo. |

|

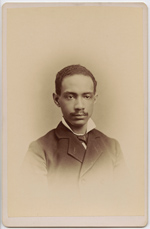

Francisco de Paula Rodríguez y Valdés, Class of 1878, the first student of color to graduate from Cornell University, was Cuban. [zoom] |

|

Aurora Brasileira. Vol. 1, No. 8, May 20, 1874. [zoom] Some foreign students, graduate and undergraduate, and some faculty, created social organizations for themselves. In 1873 the Brazilian students published Aurora Brasileira, a monthly newsletter written in Portuguese, and established Club Brasileiro, which had twenty-one members in its initial year. In 1888-89 Latin American students from Nicaragua, Puerto Rico, Honduras and Brazil created Alpha Zeta, a “foreigner’s fraternity,” although by 1894 it was no longer listed in the Cornellian. That year, a Canadian Club appears with approximately fifty members, and there is evidence that it was a strong organization for some time. In 1895 Professor E. A. Fuertes is listed as the Presidente Honorio of the Club Latino-Americano, which flourished for a time and then disappeared, only to reappear in 1916, when it was called Union Latino-Americano. The Cosmopolitan Club, founded in 1904, the first international students’ organization in this country, gave many foreign students a home at the university. It also provided an extensive program of lectures, debates, and parties which attracted many students. |

|

Elias Fausto Pacheco Jordão, Class of 1875. [zoom] The first professor of Geology at Cornell, Charles Frederic Hartt, traveled often to Brazil for exploration and study. His influence in Brazil is largely responsible for attracting Brazilian students to Cornell. One of his acquaintances in Brazil was the university’s first Brazilian student, Elias Jordão. Jordão was from São Paulo, and graduated with a degree in civil engineering. He returned to Brazil after earning his degree, and had a distinguished career as an engineer, administrator and entrepreneur. Often contributing his expertise to government initiatives, Jordão was also a politician and helped establish the São Paulo Republican Party. He died in France in 1901. As a student at Cornell, Mr. Jordão was acquainted with Anna Botsford. Ms. Botsford came to Cornell in November of 1874 for the second term; at the time, the university held three terms a year. Anna wrote that she “found a room in a house on East Seneca Street, and a place to board (i.e. to take meals) across the street.” She continued: At my boarding place were several Brazilian students. They were young and had had only a few months’ study of English. They had found their university work hard and discouraging and they were homesick. They were young, but they wore beards or mustaches or both, which made them seem much older. I found them serious, quiet, polite young men. Luckily I was not the only woman at the table, for our boardinghouse keeper always presided and one of her daughters usually sat with us.

One day, when I had been obliged to take two unexpected entrance examinations, I was low in my mind and looked longingly into the depths of the Cascadilla gorge, as I crossed the bridge. A letter from my mother was at my plate at the dinner table and I gave it a hasty glance. She had sensed my homesickness and was sympathetic. It was too much for me; I felt the tears coming and fled to the other room, ashamed of my lack of self-control, but I soon recovered and came back to the table. Lo and behold! All the Brazilian youths were weeping, their tears rolling over their beards into the soup; they were just homesick lads, although they looked like men. I had never seen men weep, and I began to laugh. They laughed too and we ate our dinner in sympathetic sadness and cheer . . . There was to be a ball in Library Hall at Thanksgiving, and E. F. Jordão, a dignified, handsome Brazilian who sat at table with me, invited me to go. I consented, for that seemed the only courteous thing to do, and sent home for my two evening dresses that I had not expected to need. In my ignorance of the social customs of Ithaca, I began to feel the need of advice. All was strange to me, and both my landlady and my boardinghouse keeper were newcomers to Ithaca. I “took my life in my hands” and called on Vice-President William Channing Russel, who looked so fierce and was really so gentle. I told him of my perplexities. He advised me not to go anywhere with Brazilian students because they were foreigners with very different customs from ours. I told him that I had promised to go this time, but that I would not go again, at which he remarked, “Advice to young people always makes them more determined to go their own way.” On the whole, however, we had an amicable conference, and it was the beginning of a long friendship. I went to the ball with Mr. Jordão, and no Puritan youth could have treated me with more courtesy and respect. I enjoyed it all greatly. The first people of Ithaca were in attendance and it seemed to me a brilliant affair. Professor Russel was certainly wrong about the Brazilian student whom I knew. They were all gentlemen, by our standards as well as their own. Anna Botsford Comstock, The Comstocks of Cornell: John Henry Comstock and Anna Botsford Comstock. An Autobiography by Anna Botsford Comstock, edited by Glenn W. Herrick and Ruby Green Smith. Ithaca, N.Y.: Comstock Publishing Associates, 1953. Read more about Anna Botsford’s experiences as one of the early women students at Cornell. |