Wine Comes to America

– Thomas Jefferson

Vitis vinifera, a species of European grape, is the standard upon which most of the world’s wine is based. Known for their ability to produce rich, complex wines, Vinifera vines were highly prized, and traveled to the New World with European colonialists from Italy, France, Germany and Spain.

The exploration of “Vinland” in 1000, by Leif Eriksson and his companions, found native grape species on the Northeast coast of North America—hence the name. However, it proved difficult to produce satisfactory wines from these wild grapes. Centuries later, early European settlers in America attempted to plant Vinifera vines in hopes of creating a familiar, quality product.

Exposed to new climates, soil types, insects, and diseases, the European Vinifera failed to take root and thrive in America. As a result, colonists made do with native species, learning how to make acceptable wines over time.

In the mid 1860s, native American grape species were transported to Europe for research purposes. Tragically, the American rootstock carried a root louse, Phylloxera Vastatrix, which attacked and fed on the vine roots. The Vinifera vines of Europe lacked the thick, fibrous root “bark” that protected the American species, and the pest soon spread throughout the vineyards of Europe, resulting in decades of decimation.

In response to the devastation, the wine growing community experimented by grafting European Vinifera vines onto native American grape rootstocks, resulting in more resistant grapevines that displayed the desirable Vinifera attributes. Today, the wine industry combines a multitude of grape varieties to create products for an increasingly wine savvy public.

|

Agoston Haraszthy. Grape Culture, Wines, and Wine-making. With Notes Upon Agriculture and Horticulture. New York: Harper, 1862. [zoom] | Additional images:

A wine enthusiast and promoter, Haraszthy traveled from his Buena Vista winery in Sonoma, California to over 165 European vineyards, gathering vine clippings that he would import to the United States. In all, Haraszthy introduced around 300 different grape varieties to California. Over time, he has become known as a founder of the California wine industry. |

|

James Lemoine. The Vine and its Fruit, More Especially in Relation to the Production of Wine: Embracing an Historical and Descriptive Account of the Grape, its Culture and Treatment in All Countries Ancient and Modern… London: Longmans, Green, 1875. [zoom] The color map in this reference book on wine details the principal wine districts of Europe. |

|

Henry Vizetelly. A History of Champagne With Notes on the Other Sparkling Wines of France. London: Vizetelly; New York: Scribner & Welford, 1882. [zoom] In 1662, Christopher Merret, an English physician and scientist, created the méthode champenoise, or the process of a second fermentation in the bottle with the addition of sugar. The result was a sparkling wine which took its name from the Champagne appellation. Vizetelly describes the Champagne region’s culture, history, and wine making practices: “Good Champagne does not rain down from the clouds, or gush out from the rocks, but is the result of incessant labour, patient skill, minute precaution, and careful observation. In the first place, the soil imparts to the natural wine a special quality which it has been found impossible to imitate in any other quarter of the globe.” |

|

Landmarks. Iona, N.Y.: [C.W. Grant], 1862-1864. [zoom] | Additional images:

J.C. Massa. Landmarks Calender [sic] and Other Useful Information Relative To Grapes and Other Fruits. 1868. This book records the trials and progress of a 19th century grape grower. The first half of the book is in viticulturist Massa’s hand, detailing the grape propagation process, listing monthly vineyard tasks, and commenting about the science of grafting vines. The latter half of the volume includes the periodical, Landmarks, which discusses horticulture and pomological issues facing upstate New York in the 1860s. On loan from the Frank A. Lee Library, Agricultural Experiment Station, Geneva, N.Y. |

|

New York State Agricultural Experiment Station, Geneva, N.Y. Vinifera Grapes in New York. Bulletin 432. Washington, D.C.: Department of Agriculture, 1917. [zoom] This bulletin discusses early attempts to grow Vitis vinifera vines in upstate New York. First experiments failed due to downy and powdery mildew, black rot, phylloxera, and winter injury. Learning by trial and error, the NYS Agricultural Experiment Station viticulturists produced hardier plants which were more disease resistant by grafting Vinifera vines onto native rootstocks. |

|

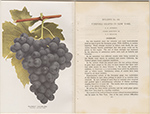

United States patent: Einset Seedless Grape, plant 6,160. April 26, 1988. [zoom] | Additional images:

The genetic engineering and testing required to create new grape varieties involves a large investment of time and research. Once a new variety has produced acceptable fruit, an extensive trial period follows. Characteristics of the new species are examined over time, with breeders evaluating fruit quality, sugar content, sensitivity to herbicides, resistance to winter injury, maturation period, and resistance to insects and diseases. Patents like this one trace the genetic lineage of a new variety, placing the grape in context and describing all of its physical characteristics. The accompanying image is for a different grape variety. |

|

Reproduction from John R. Hailman. Thomas Jefferson on Wine. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2006. [zoom] | Additional images:

Jefferson was a life-long lover of wines. His position as Minister to France (1785-1789) provided him with the opportunity to hone his palate and advance his wine education. Upon returning home to Monticello, he enthusiastically began experimenting with plantings of Europe’s finest Vitis vinifera vines on the grounds of his Virginia plantation. Unfortunately, he encountered the same frustrations that other growers had faced when conducting similar experiments in other areas of the country; the finicky Vinifera vines did not thrive on American soil. Unwilling to accept defeat, Jefferson tried producing drinkable wine from native species, periodically returning to his Vinifera trials. |