Selection in Relation to Sex

Darwin was the first naturalist to describe and fully explore sexual selection. He realized that “secondary sexual characteristics,” those not involved in the act of reproduction, also often differed significantly between sexes. This was called dimorphism. The bulk of Descent of Man was devoted to illustrating that either competition for mates (often in the form of males fighting), or mate choice (as in a female beetle choosing the male with the longest snout), resulted in particular characteristics being selected in each gender. He described sexual selection in a vast array of animals as supporting evidence for his notion that it had been a powerful force behind the formation of the human races. At the same time, he was aware that sexual selection did not account for all racial differences.

|

Anti-slavery token in copper, issued in the United States. [zoom] Darwin came from a family of active abolitionists. In 1787 his grandfather, Josiah Wedgwood, produced in his Staffordshire pottery works a famous jasperware medallion embossed with this image. Almost a century later, Darwin supported the northern American states during the Civil War because he abhorred slavery. |

|

Robert FitzRoy. Narrative of the Surveying Voyages of his Majesty’s Ships Adventure and Beagle… London: H. Colburn, 1839. [zoom] Darwin was fascinated by the Yahgan people (then called “Fuegians” by Europeans) in South America’s Tierra del Fuego. Growing up in northern England in the nineteenth century, Darwin had limited contact with people of other races. On the Beagle voyage, however, he could observe people throughout the world, and he became as interested in human variation as he was in variation throughout the plant and animal kingdoms. Unlike many Victorians, he concluded that the human races were all of the same species. |

|

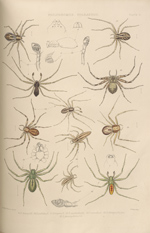

Blackwall, John. A History of the spiders of Great Britain and Ireland. London: R. Hardwicke, 1864. [zoom] | Additional images:

Beginning with the lower animals, Darwin searched for differences in secondary sexual characteristics. He found that the genders of some spiders differed, as in the Sparassus species, the two green spiders found at the bottom of this page. The female on the left was larger than the more colorful male on the right. |

|

Charles Darwin. The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex. New York: D. Appleton and Company, 1873. [zoom] | Additional images:

With these illustrations, Darwin compared the males to the females in five different species of beetles. None of these beetles were known to fight one another for mates, and the horns and knobs on the heads were highly variable within a species. Darwin concluded that the horns and knobs were a result of sexual selection, and had been acquired as ornaments: “This view will at first appear extremely improbable; but we shall hereafter find with many animals, standing much higher in the scale, namely fishes, amphibians, reptiles and birds, that various kinds of crests, knobs, horns and combs have been developed apparently for this sole purpose.” |

|

Transactions of the Zoological Society of London. London: 1869. Vol. 6, plate 87. [zoom] Darwin used this illustration of a dimorphic fish, the green swordtail (Xiphophorus hellerii), in Descent of Man. Two female forms are illustrated above the male. |

|

Eastern Bluebird (Sialia sialis). [zoom] | Additional images:

New York’s state bird displays dimorphic colors that become especially pronounced during the breeding season. Specimens courtesy of the Cornell University Museum of Vertebrates. |