Domesticated Animals and Plants

Darwin started working on The Variation of Animals and Plants under Domestication soon after the Origin was published, but it took eight years to complete the book. His intent was to explore the artificial selection of variations, in order to learn more about natural selection. The breeders of animals and plants became his teachers as he studied the variation of domestic animals, and their differences and derivation from their wild ancestors. With this work, Darwin explored the nature of inheritance, and devised his hypothesis of “pangenesis” as a possible means by which traits were passed to the next generation.

|

Allan Octavian Hume. The Game Birds of India, Burmah, and Ceylon. Calcutta: A. O. Hume and C. H. T. Marshall, 1879-81. [zoom] Darwin studied the history of fowl, investigated breeds that were known throughout the world, examined English breeds, and crossed several different breeds at Down House. He concluded that the red junglefowl (now Gallus gallus bankiva) from Southeast Asia was the common ancestor of domestic chickens. |

|

Charles Darwin. The Variation of Animals and Plants under Domestication. London: J. Murray, 1868. First edition. [zoom] | Additional images:

Darwin closely compared several varieties of fowl, including the Spanish, Hamburgh, and Polish. |

|

Charles Darwin. The Variation of Animals and Plants under Domestication. London: J. Murray, 1868. First edition. [zoom] The perforated skull of a Polish cock (above) compared to the skull of its ancestor the red junglefowl, or Gallus bankiva (below). Darwin discovered that as breeders selected for more elaborate head crests, associated changes took place in the birds’ skulls, which became increasingly perforated and knobby. |

|

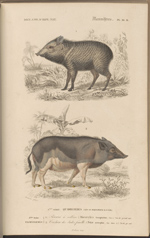

Charles Darwin. The Variation of Animals and Plants under Domestication. London: J. Murray, 1868. Vol. 1. First edition. [zoom] The head of a wild boar (above) compared to the head of a “Yorkshire Large Breed.” Darwin noted how much the facial structure changed as wild pigs were domesticated. |

|

Charles d’Orbigny. Dictionnaire Universel d’Histoire Naturelle... Paris: MM. Renard, Martinet ..., 1849. [zoom] Dicotyles torquatus, an old name for the collared peccary of the Americas, is illustrated on top. Sus scropha, the wild boar of Europe and Asia, is illustrated on the bottom. After studying wild and domestic pigs, Darwin concluded that domestic breeds had derived from the group to which Sus scrofa belonged, and from another Asian form. |

|

William Youatt. The Pig: a Treatise on the Breeds, Management, Feeding, and Medical Treatment, of Swine; with Directions for Salting Pork, and Curing Bacon and Hams. London: Cradock and Co., 1847. [zoom] Darwin consulted William Youatt’s books on the pig and other domesticated animals which he subsequently discussed in Variation. |

|

Burt Green Wilder. “Extra digits.” June 2, 1868. Extracted from the Publications of the Massachusetts Medical Society, Vol. II, no. 3. [zoom] In the second edition (1875) of Variation, Darwin cited this paper by Professor Wilder at Cornell. Wilder had tabulated information on extra digits (polydactylism). Darwin wrote: “Dr. Burt Wilder has tabulated a large number of cases, and finds that supernumerary digits are more common on the hands than on the feet, and that men are affected oftener than women. Both these facts can be explained on two principles which seem generally to hold good; firstly, that of two parts, the more specialised one is the more variable, and the arm is more highly specialised than the leg; and secondly that male animals are more variable than females.” |

|

Burt Green Wilder’s Classroom. [zoom] Burt Green Wilder (1841-1925), Cornell’s first professor of comparative anatomy and zoology, teaching a class in McGraw Hall’s zoology lecture room. |

|

Burt Green Wilder (1841-1925). [zoom] |