Plants Climb and Plants Move

Darwin grew interested in the movement of plants by studying the evolution of climbing plants, by examining all types of movement in a wide variety of species, and through his work on insectivorous plants. He was curious about the development of movement in plants. Why was it an advantage for a plant to move, and how did a plant species develop the ability to move?

In studying climbing plants, he divided them into several categories. Darwin concluded that leaf-climbers had derived from twining plants (twining being the simplest form of climbing), and that tendril-bearing forms had evolved from leaf-climbers.

|

Portrait of Charles Darwin’s Son, Francis (1848-1925).

Francis Darwin moved back to Down House as an adult and worked with his father on several botanical projects. After his father died, Francis became a lecturer and then a reader in botany at the University of Cambridge. |

|

John Lindley. Edwards’s Botanical Register… London: J. Ridgeway and Sons, 1836. Vol. IX. [zoom] A spiral-twining plant from the genus Manettia. Darwin determined that the stem of a species of Manettia (in family Rubiaceae, the madders) followed the sun, moving in a circle over a period of six to seven hours. |

|

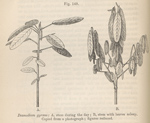

Canary-Bird Flower (Tropaeolum peregrinum). [zoom] Darwin observed and measured the climbing movements of seven species of the leaf-climbing genus Tropaeolum (which includes nasturtiums). On loan from L.H. Bailey Hortorium Herbarium, Cornell University. |

|

Wild Cucumber (Echinocystis lobata). [zoom] The Harvard botanist Asa Gray sent Darwin seeds of Echinocystis lobata, the wild cucumber from North America. While ill, Darwin watched its tendrils twining about his study: “Their irritability is beautiful, as beautiful in all its modifications as anything in orchids.” On loan from L.H. Bailey Hortorium Herbarium, Cornell University. |

|

Asa Gray (1810-1888). [zoom] While the botanist Asa Gray (1810-1888) was the major supporter of Darwin’s ideas in the United States, he believed that a divine force played a role in evolution. During the 1860s, Gray and Darwin engaged in an extensive correspondence regarding design in nature. Portrait from Charles Darwin. More Letters of Charles Darwin … New York: D. Appleton, 1903. |

|

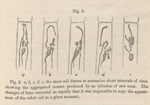

Journal of the Linnean Society of London. Botany [London, New York]: Academic Press, 1882. [zoom] In one of his last two published papers, read to the Linnean Society by Francis Darwin, Charles Darwin examined cellular changes in the common sundew when substances were placed on the leaves. A “time lapse” drawing illustrated what he called “aggregation” in the cells of the glandular hairs. |

|

Charles Darwin. The Power of Movement in Plants. London: J. Murray, 1880. First edition. [zoom] Darwin’s third son, Francis, was credited on the title page of The Power of Movement in Plants as assisting the author. The two Darwins meticulously measured the movement of roots, stems, petioles, and leaves in a wide range of plants, including movements made to “sleep.” |