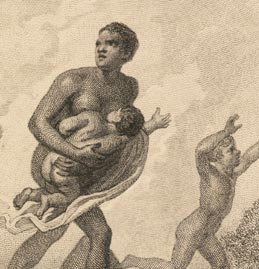

Origins of Abolitionism

![]()

The Slave Trade Act did not render slavery itself illegal, however, and

abolitionists in England still faced many years of struggle. In 1824,

the abolitionist Elizabeth Heyrick (1769-1831) challenged the prevailing

“gradualism,” or support for a gradual end to slavery, when

she published the pamphlet Immediate, not Gradual Abolition. Her call

for an immediate end to slavery, accepted in most female abolitionist

organizations, was widely resisted in the more powerfully connected, male-dominated

societies. Through persuasion and political maneuvering, however, Heyrick’s

ideas gained ground, and abolitionist leadership finally embraced “immediatism.”

After decades of battle in Parliament against powerful proslavery lobbies, British abolitionists finally realized their ultimate goal. In 1833, the Abolition of Slavery Act was passed, initiating a plan to free all slaves over the next four years and to compensate slave owners financially for their “property” losses.

The abolitionists’ victory in Britain did not go unnoticed in America. While continuously publishing British anti-slavery materials, American activists celebrated and commemorated West Indian emancipation, knowing that the same could—and would—be achieved in the United States.

![]()

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

Copyright

© 2002 Division of Rare & Manuscript

Collections

2B Carl A. Kroch Library, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY, 14853

Phone Number: (607) 255-3530. Fax Number: (607) 255-9524

For

reference questions, send mail to:

rareref@cornell.edu

For questions or comments about the site, send mail to: webmaster.