Mathew Brady

“From the first I regarded myself as under obligation to my country

to preserve the faces of its historic men and mothers.”

– Mathew Brady, 1891

Mathew Brady (1823-1896), the “prince of photographers,” as the New York Times called him in 1862, was the most important figure in the history of American photography. He revolutionized the business of photography.

Brady created a new structure for the industry, hiring dozens of highly skilled photographers who operated under the Brady brand. This structure was vital to Brady’s effort to document the Civil War. Demonstrating that photography could go beyond posed portraits and landscapes, he was one of the first photojournalists. Brady helped to invent modern advertising with his newspaper advertisements and elaborate credit lines. He transformed the retail side of photography, making his studio’s waiting room a social venue featuring his work in a vast salon-gallery. Finally, he was a pioneering historian in his use of photography to document the likenesses of “historic men and mothers,” as he declared.

In the early 1840s Brady learned the science of the daguerreotype from Samuel Morse, the inventor of the telegraph. Brady made his early reputation with superb portraits of the great figures of his time, such as John Calhoun and Andrew Jackson. With the invention of paper photography from glass negatives in the mid 1850s, Brady was able to produce unprecedented large-format portraits in unlimited quantities.

Brady’s greatest triumph was the endeavor that ultimately bankrupted him—his project to document the Civil War. Brady’s corps of photographers and their mobile studios followed the Union Army across the nation’s battlefields. Brady’s war photographs profoundly shaped views of war, both in Brady’s day and today. They provided the first opportunity for a large number of Americans to see firsthand the brutality of war. Brady mortgaged his future to fund the project, and he lost that fortune after the war when neither the federal government nor the war-weary public had an appetite to purchase photographs of the recent conflict.

“When the history of American photography comes to be written,” commented Harper’s Weekly in 1863, “Brady more than any other man, will be entitled to rank as its father.”

|

Napoleon Sarony. Mathew Brady, ca. 1870. [zoom] Albumen print, cabinet card mount This photograph of Brady was taken by Sarony, one of Brady’s leading competitors in New York. By this time Brady was under great financial strain. He had mortgaged his future on his vast archive of Civil War photographs, but the public no longer desired them. In 1876 Congress purchased his negatives for $25,000, thereby preserving them for posterity, but the entire sum was swallowed up by Brady’s debts. Brady died impoverished in 1896. |

|

Mathew Brady. Samuel F. B. Morse, 1860s. [zoom] Albumen print, carte de visite mount Samuel Morse (1791-1872) met Daguerre in March of 1839 while in Europe obtaining patents for his invention of the telegraph. One of the first Americans to see a daguerreotype, Morse returned home to become one of America’s earliest daguerreotypists. He improved the process, opened America’s first daguerreotype studio, and taught photography classes. His students included such luminaries as Mathew Brady, Edward Anthony of E. & H. T. Anthony & Company, and Albert Southworth of Southworth and Hawes. |

|

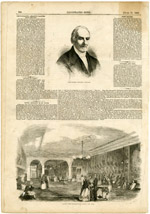

“Brady’s New Daguerreotype Saloon.” Illustrated News. New York: June 11, 1853. [zoom]

In Brady’s lavishly appointed New York gallery, visitors not only sat for their own portraits, but also saw Brady’s portraits of the great men and women of the day. Soon after this article appeared, the invention of albumen paper and the cartes de visite permitted Brady to sell copies of his portraits to the public. Brady was poised to take full advantage of the technology that would soon revolutionize photography. |

|

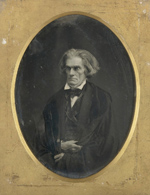

Mathew Brady. John C. Calhoun, 1849. [zoom] Daguerreotype, whole plate This is the most famous photograph of John C. Calhoun (1782-1850), the great American statesman who served as vice president, secretary of state and of war, congressman, and senator from South Carolina. Brady himself surely operated the camera when the legendary political leader came to his studio. He recalled that, “Calhoun’s eye was startling, and almost hypnotized me.” The Photographic Art-Journal praised the image’s “depth and earnestness, and intensity, and spiritualism, which so eminently distinguish [Calhoun] from almost all other men.” Brady chose this luminous portrait to be the basis for one of the twelve lithographs in his Gallery of Illustrious Americans (1850). On loan from the Stephan and Beth Loewentheil Family Photographic Collection. |

|

Mathew Brady and assistants. Mathew Brady Sample Book, ca. 1860. [zoom]

Brady’s National Photographic Gallery in Washington used this unique album for its own reference and possibly as a source book from which the public could select and order cartes de visite. The volume contains 480 photographs including Abraham Lincoln and his wife, Jefferson Davis, Stonewall Jackson, Millard Fillmore, Commodore Perry, P.T. Barnum, James Fenimore Cooper, Abner General Doubleday, U. S. Grant, and many other statesmen, generals, authors, and entertainers. |

|

Mathew Brady. Brady Imperial Portrait, ca. 1857. [zoom] Hand-colored salted paper print, 18 1/2 x 15 5/8 in. The introduction of glass negatives made it possible to produce larger and more impressive images. Brady created a high-end portrait format prized by the elite. His exceedingly large “Imperial Photograph” cost several hundred dollars, a tremendous sum in the mid 19th century. Usually 17 x 20 inches, the most extravagant, meticulously hand-painted examples competed in the market with portraits painted in oils. Upon viewing one of Brady’s “life size portraits,” one commentator in Harper’s Weekly (1857) remarked, “The vocation for the portrait painter is not gone but modified. Portrait painting by the old methods is as completely defunct as is navigation by the stars.” |

|

Mathew Brady. Seven Women, ca. 1857. [zoom] Ambrotype, half plate |

|

Photograph by Mathew Brady, published by E. & H.T. Anthony. “The Fairy Wedding Group,” 1863. [zoom] Albumen print, carte de visite The immensely popular Charles Stratton (1838-1883) and Lavinia Warren Stratton (1841-1919), better known as General and Mrs. Tom Thumb, made front-page news when they were married in 1863. After the wedding the Strattons were received by Lincoln at the White House. The printing of facsimile signatures on the reverse reflects the popularity of cartes as souvenirs of celebrities. Anthony, the publisher of this carte, produced more than 3600 cartes per day from a collection of more than 4000 images licensed from Brady and other photographers. |

|

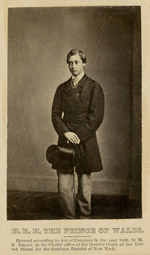

Mathew Brady. Prince of Wales, 1860. [zoom] Albumen print, carte de visite mount Brady assiduously courted the famous men and women of his day, flattering them into siting for photographs and displaying and selling their portraits in his galleries. His sitters in turn were persuaded that their own status deserved none other than the “prince of photographers.” During his visit to the United States, the Prince of Wales made an unsolicited visit to Brady’s gallery to have portraits made. |