Photography As Art, Painting As Impression

For early photographers, long exposure times, intense frontal lighting, and small image sizes left little opportunity for artistic expression. But as technology improved, so did the artistic potential of the medium.

The shift in the 1870s from cartes de visitetoomuch larger formats gave photographers more creative space in which to work. The artistic quality of portraits improved dramatically from the neck-clamp days, as decreased exposure times allowed for more movement and creativity in the posing of subjects.

Portrait photographers began to use filters and special lenses to soften their subject’s images. Creative lighting effects and better print quality further brought photography into the realm of art.

The rise of photography threatened the livelihood of professional portrait painters. Upon seeing his first daguerreotype, French painter Paul Delaroche had remarked that, “painting is dead from this day.” For many 19th century painters, photography meant declining portrait commissions and commercial disaster.

For other painters, the rise of photography as art meant artistic liberation. As accurate imitation of nature became the unchallenged domain of photography, artists began to explore how painting could go beyond the old ideal of “holding a mirror up to nature.” They increasingly explored mood, color and light in more subjective and non-representational ways. The stage was set for the Impressionist Movement of the 1870s and 1880s, during which painting—now superseded as a representational art-form—would break ground as a creative one.

|

Napoleon Sarony. Sarony Studio Sample Board, 1866-1871. [zoom] Albumen print, 13 7/8 x 17 in. Likely created for the public to order photographs, this sample board illustrates Sarony’s eccentric style. He positioned his sitters in unconventional poses and elicited unusually animated expressions. Specializing in photographs of actors and actresses, he became one of America’s most famous photographers. |

|

Napoleon Sarony. Harriet Beecher Stowe, ca. 1880-1885. [zoom] Albumen print, cabinet card mount This portrait of Harriet Beecher Stowe (1811-96), author of Uncle Tom's Cabin, illustrates Sarony’s talent and continued departure from the standard portrait techniques. Photographed using the new “Rembrandt Lighting” technique, the subject was lit from the side and a reflector was used to bounce light softly into the shadows to show slight detail. |

|

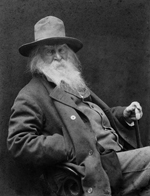

George C. Cox. Walt Whitman, 1887. [zoom] Platinum print, 9 x 7 in. This photograph of poet Walt Whitman (1819-1892) demonstrates the artistic advancements made possible by improvements in photographic technology. Whitman’s friend Jeanette Gilder witnessed the session: “... he never posed for a moment. He simply sat in the big revolving chair and swung himself to the right or to the left.” The highly sensitive dry plate negative required only a short exposure time, allowing the photographer to capture a subject in natural poses. No longer was the subject required to be clamped and held still for several seconds. On loan from the collection of Susan Jaffe Tane |

|

Claude Monet (1840-1926). “Impression Sunrise,” 1872. [zoom] |

|

Thomas Doughty (1793-1856). “View in Maine,” ca. 1835. [zoom] |

|

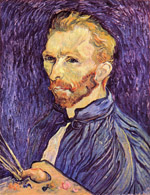

Vincent Van Gogh (1853-1890). “Self-portrait,” 1887. [zoom] |

|

Chester Harding (1792-1866). “Chief Justice John Marshall,” 1833. [zoom] |

|

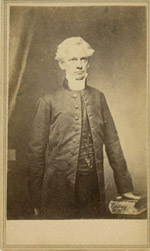

Brady's Gallery. Bishop Alonzo Potter, 1860s. [zoom] Albumen print, carte de visite mount This carte de visite typically borrowed its esthetic from portrait painting, as comparison of these portraits of John Marshall and Alonzo Potter shows. |